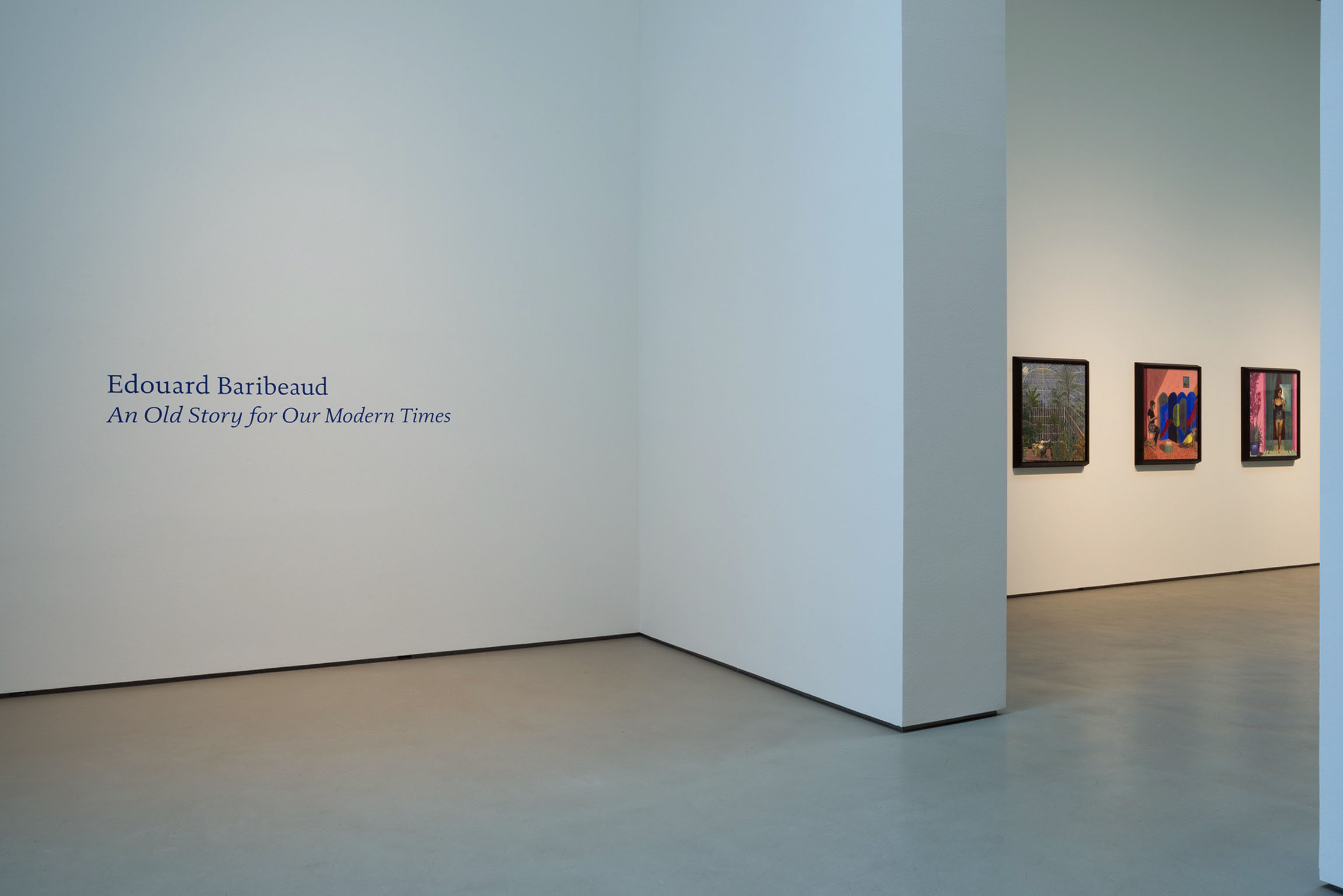

Edouard Baribeaud

An Old Story for Our Modern Times

Works

Danaë

2018

Watercolor and gold leaf on paper

80 × 72 cm

The Navel of the World

2018

Ink and watercolor on paper

78 × 71 cm

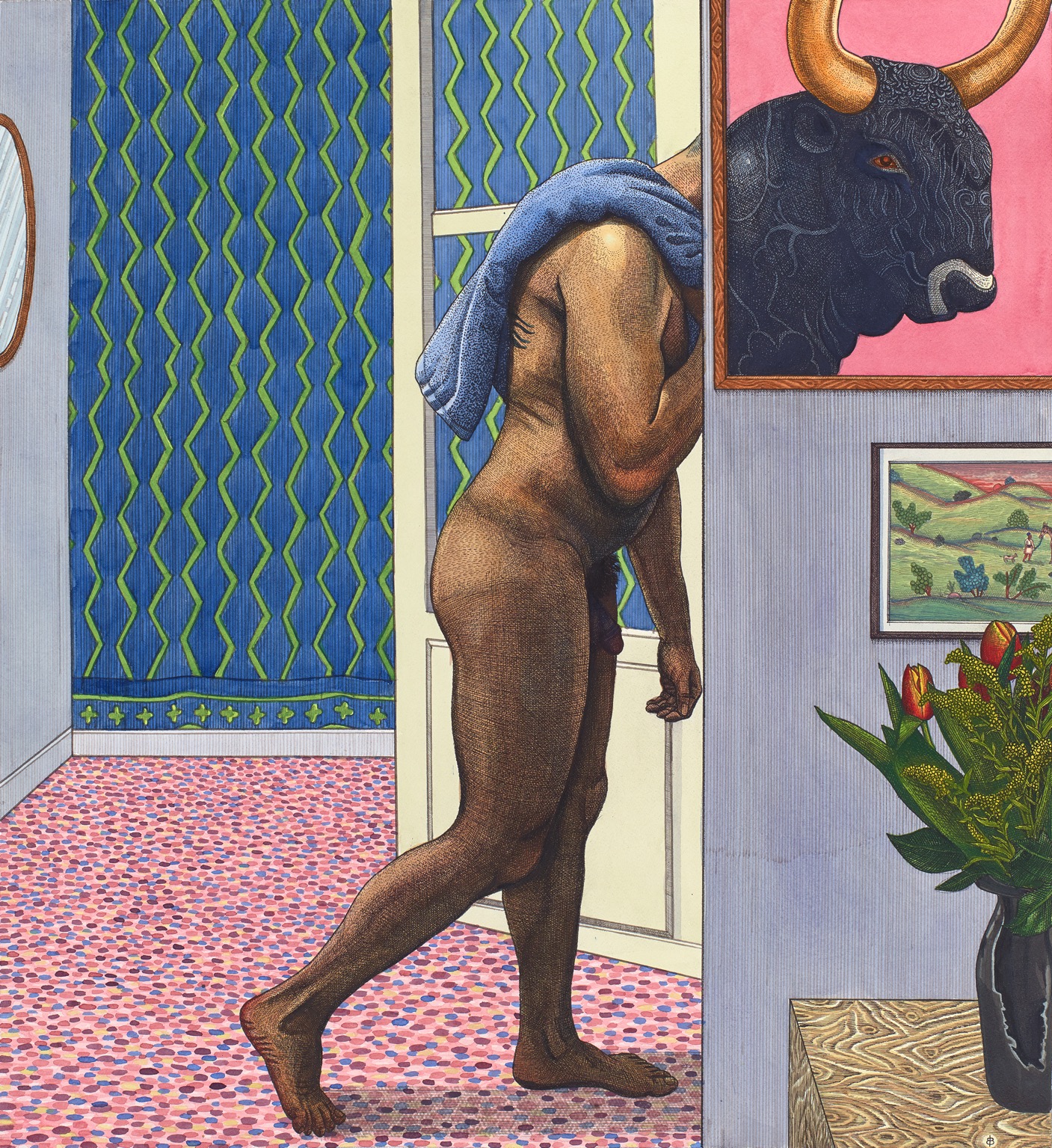

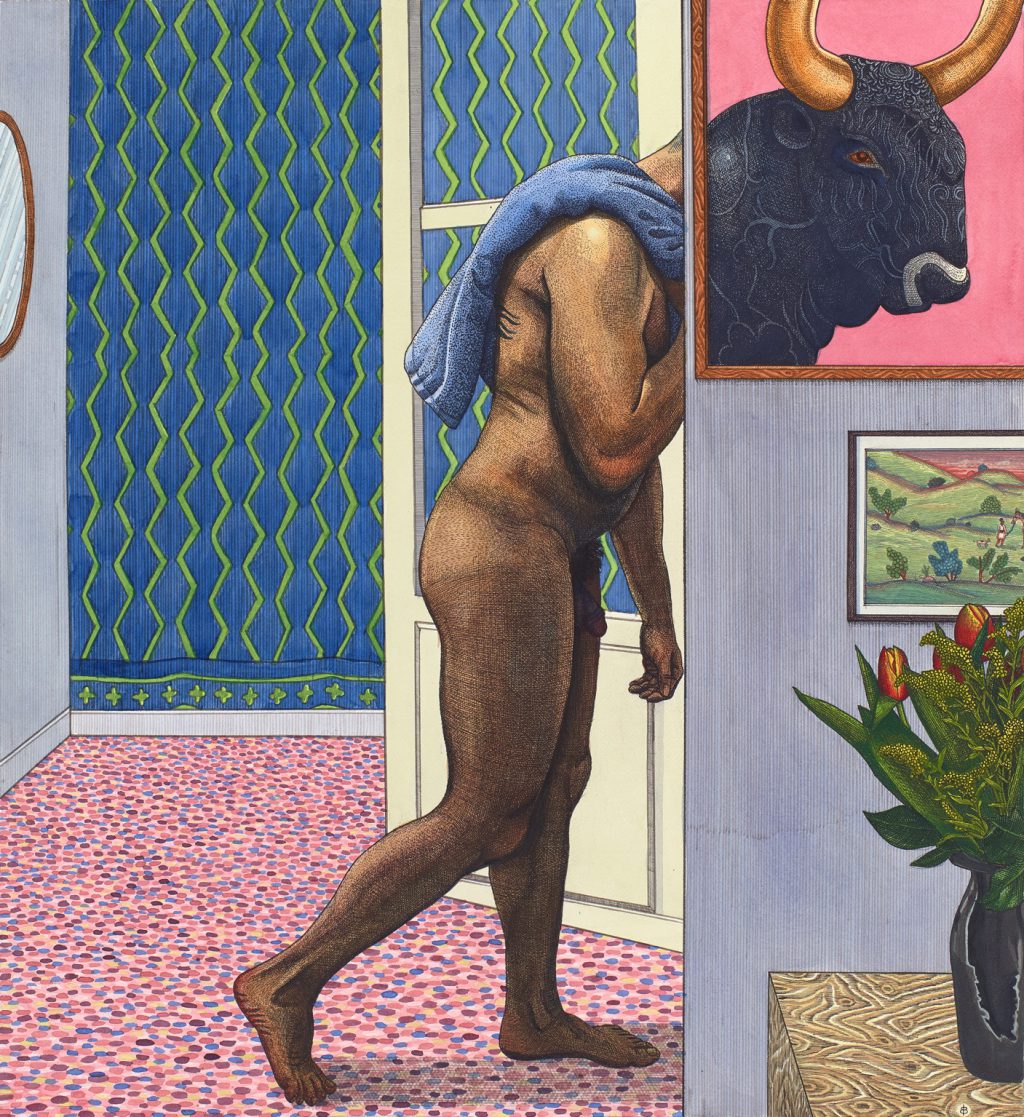

Minotaur

2018

Ink and watercolor on paper

77.5 × 71 cm

Daedalus

2018

Ink, watercolor and goldleaf on paper

78 × 71 cm

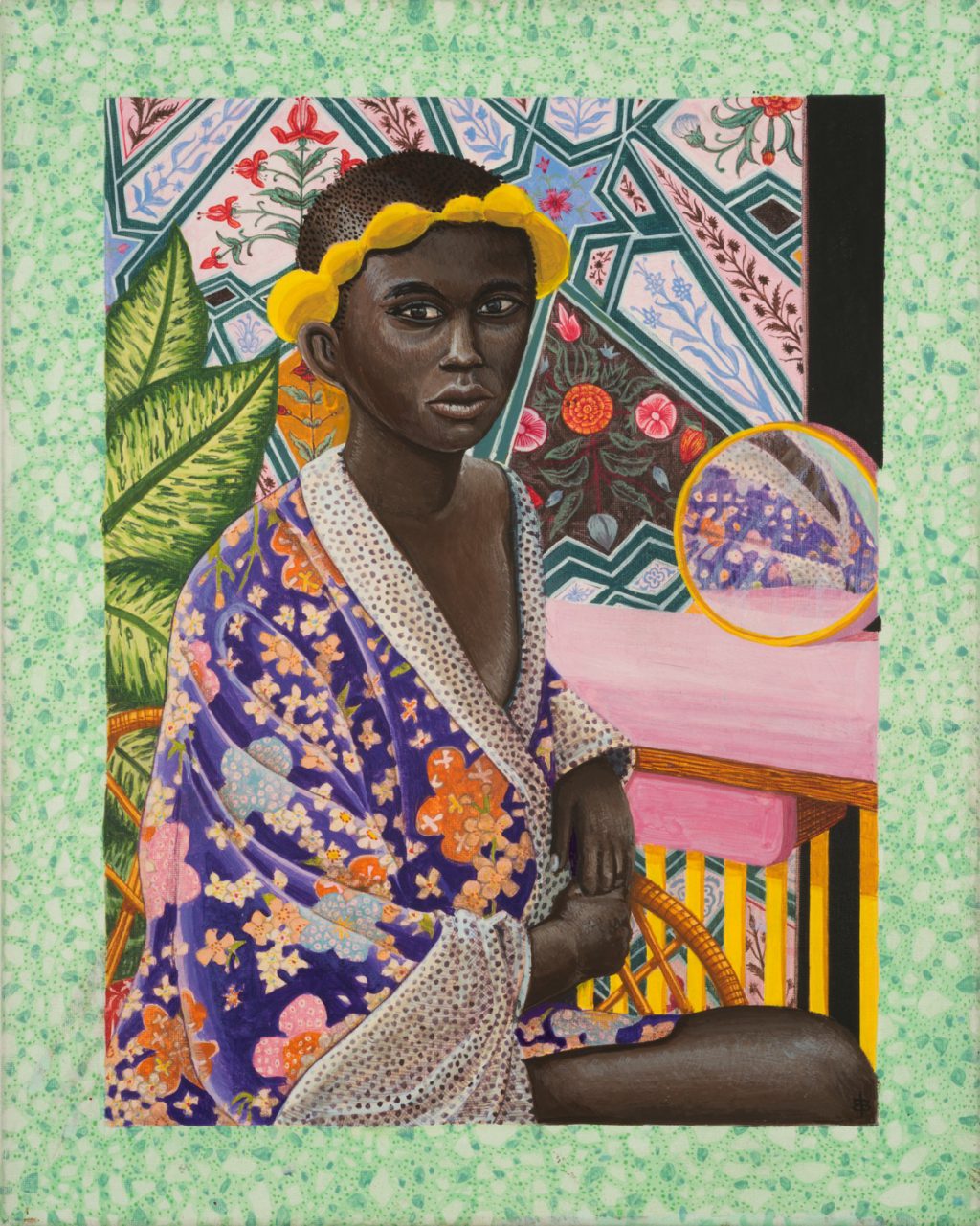

Penelope

2018

Egg tempera and embroidery on canvas

Embroidery by Marie Berthouloux, Ekceli

Charon

2018

Egg tempera on canvas

160 × 200 cm

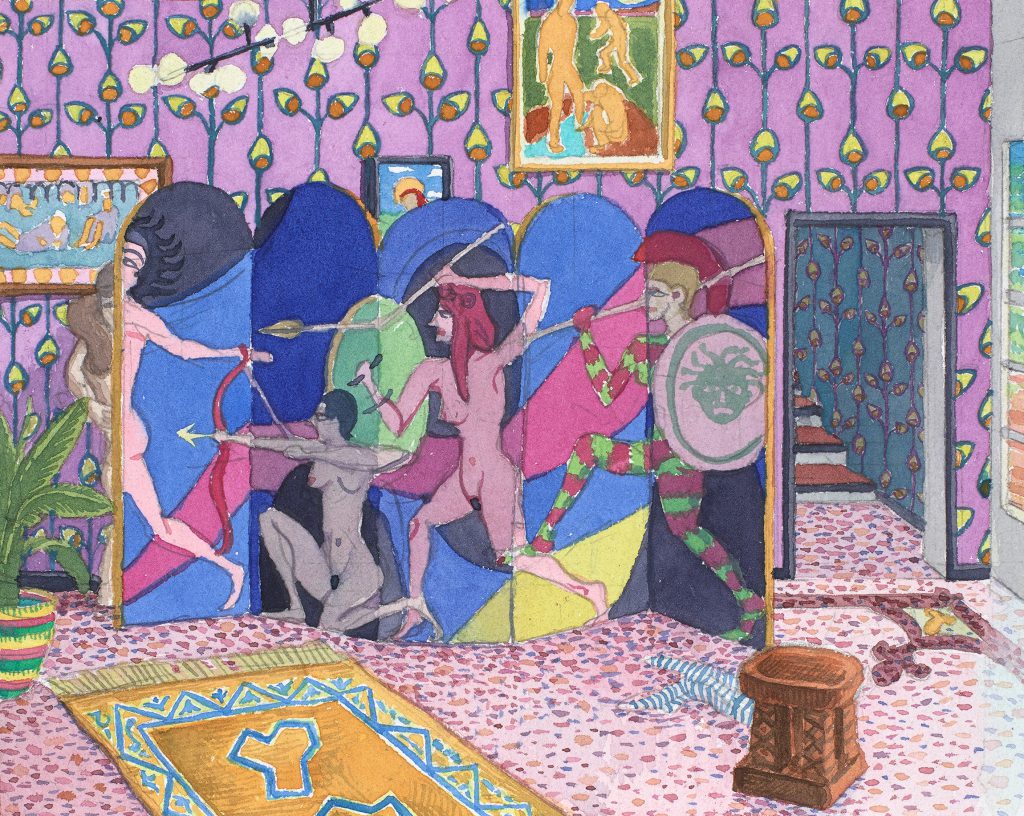

Penthesilea

2018

Egg tempera on canvas

160 × 200 cm

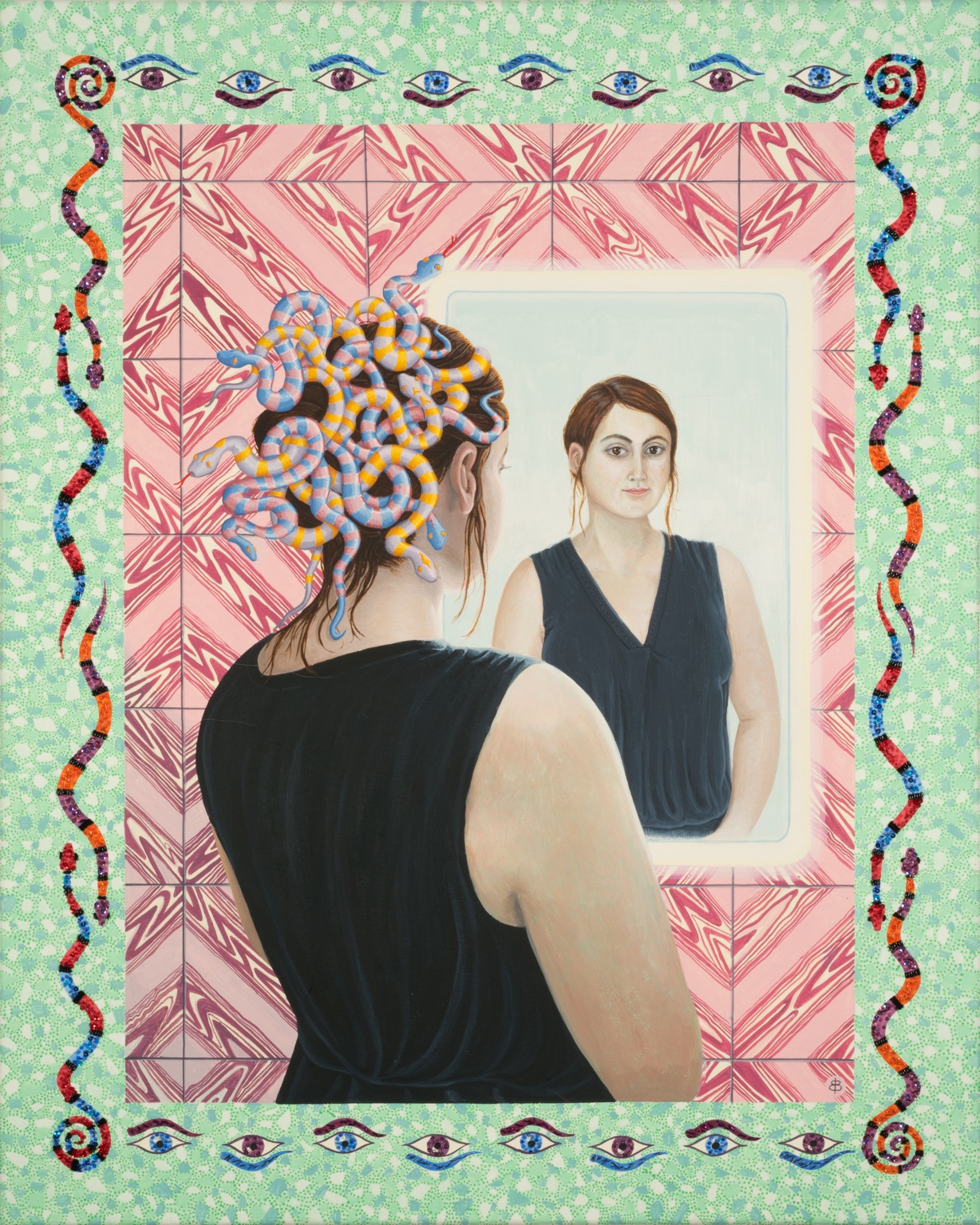

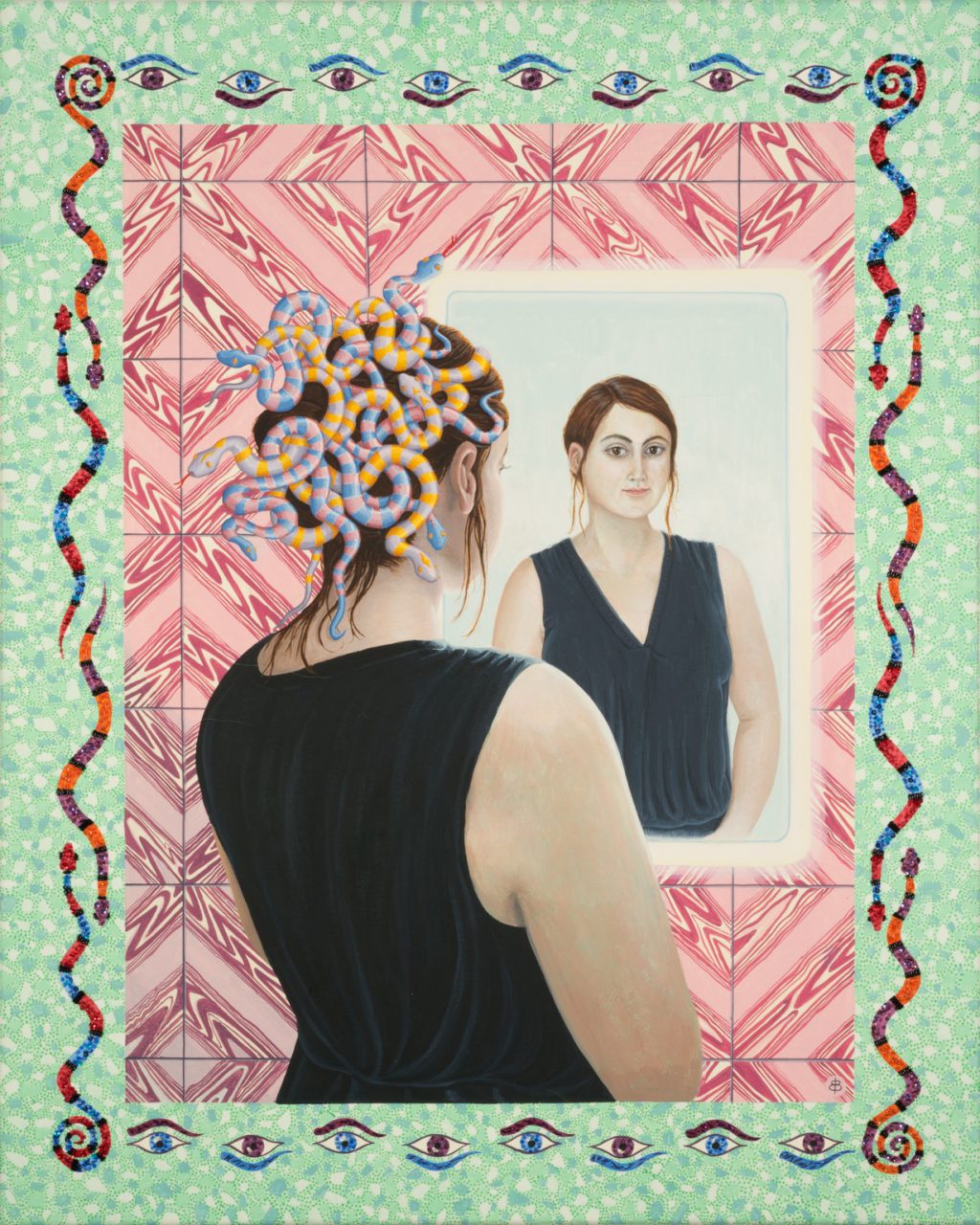

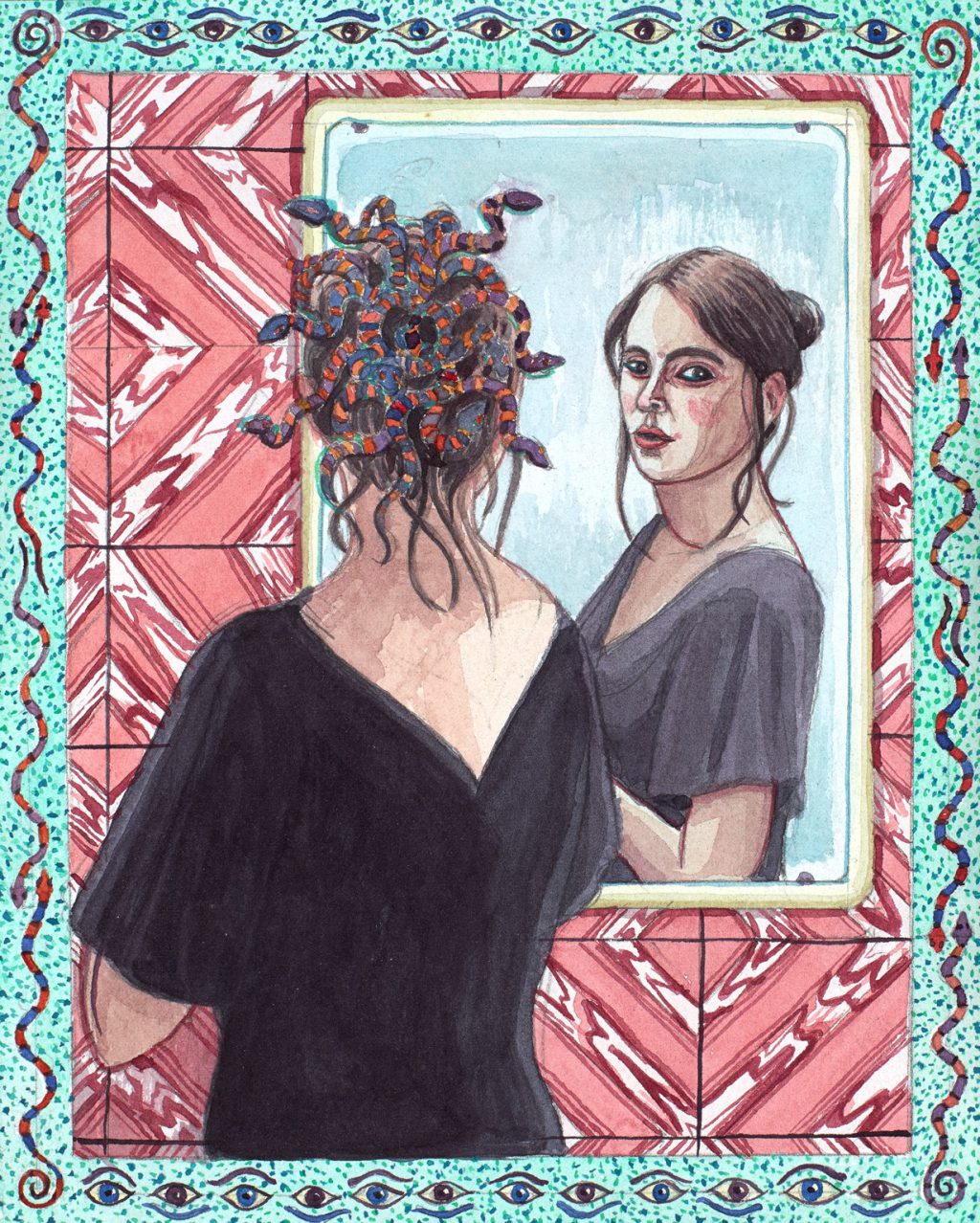

Medusa

2018

Egg tempera and embroidery on canvas

Embroidery by Marie Berthouloux, Ekceli

100 × 80 cm

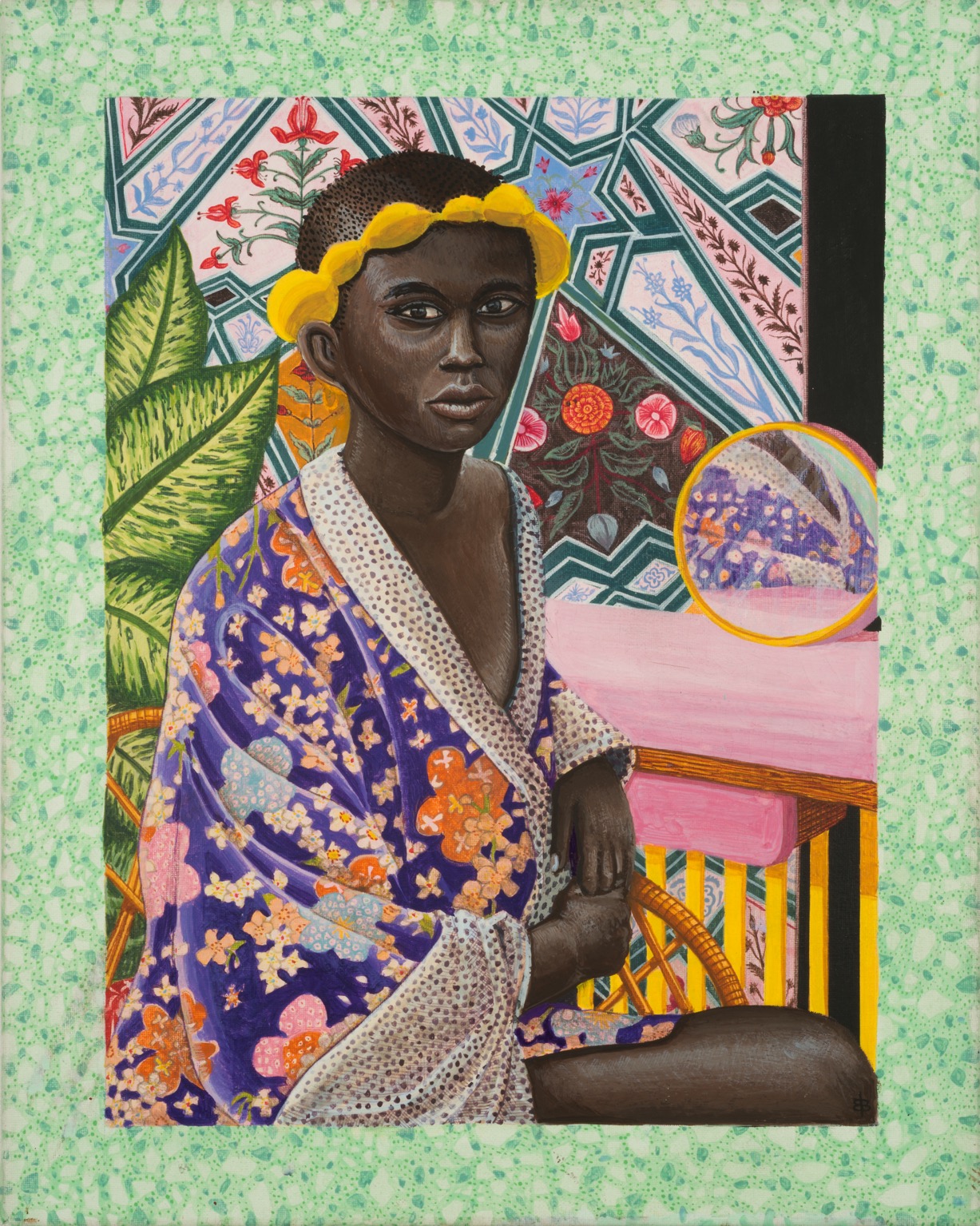

Narcissus

2018

Egg tempera on canvas

49.5 × 39.5 cm

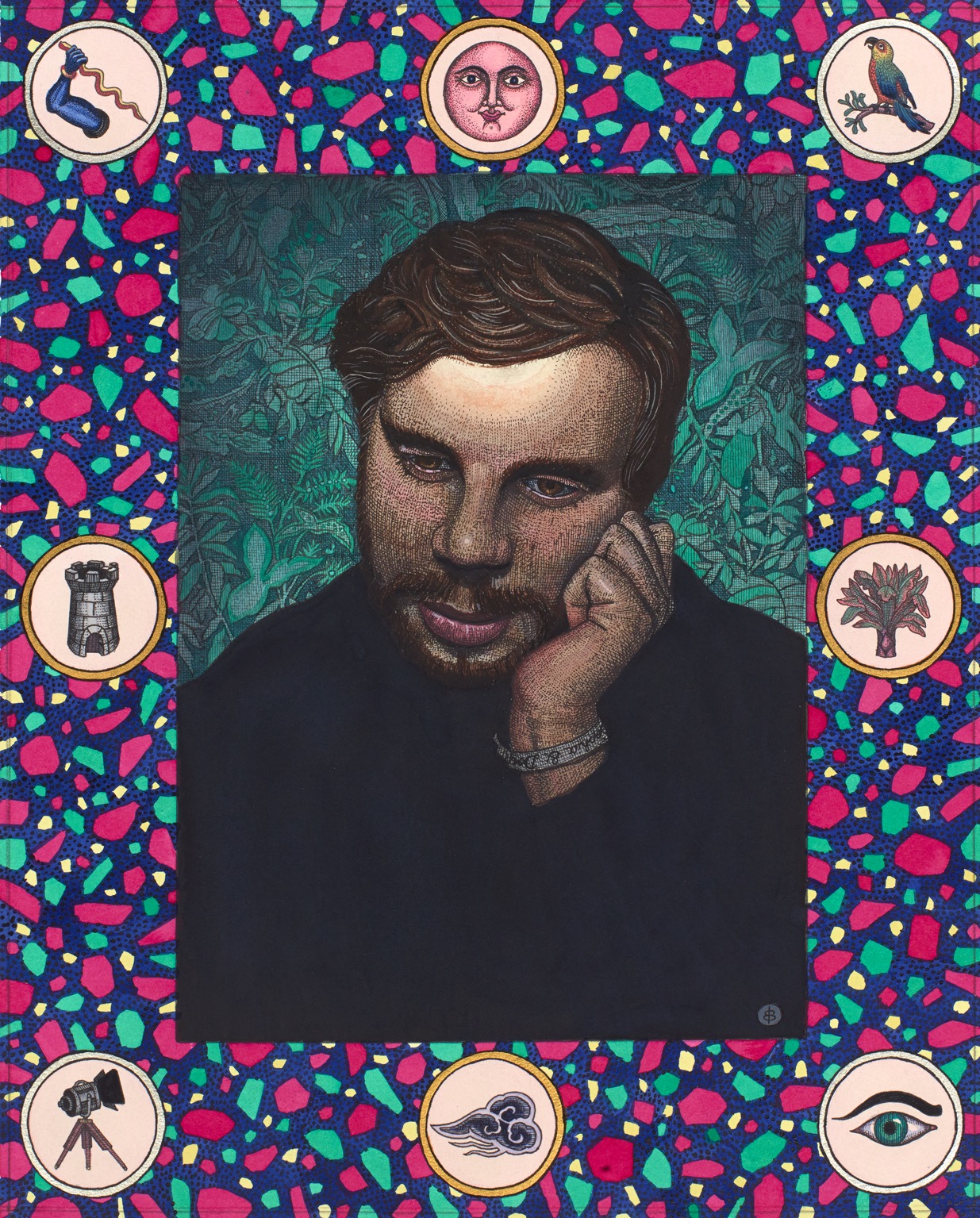

Homer

2018

Ink and watercolor on paper

49.5 × 39.5 cm

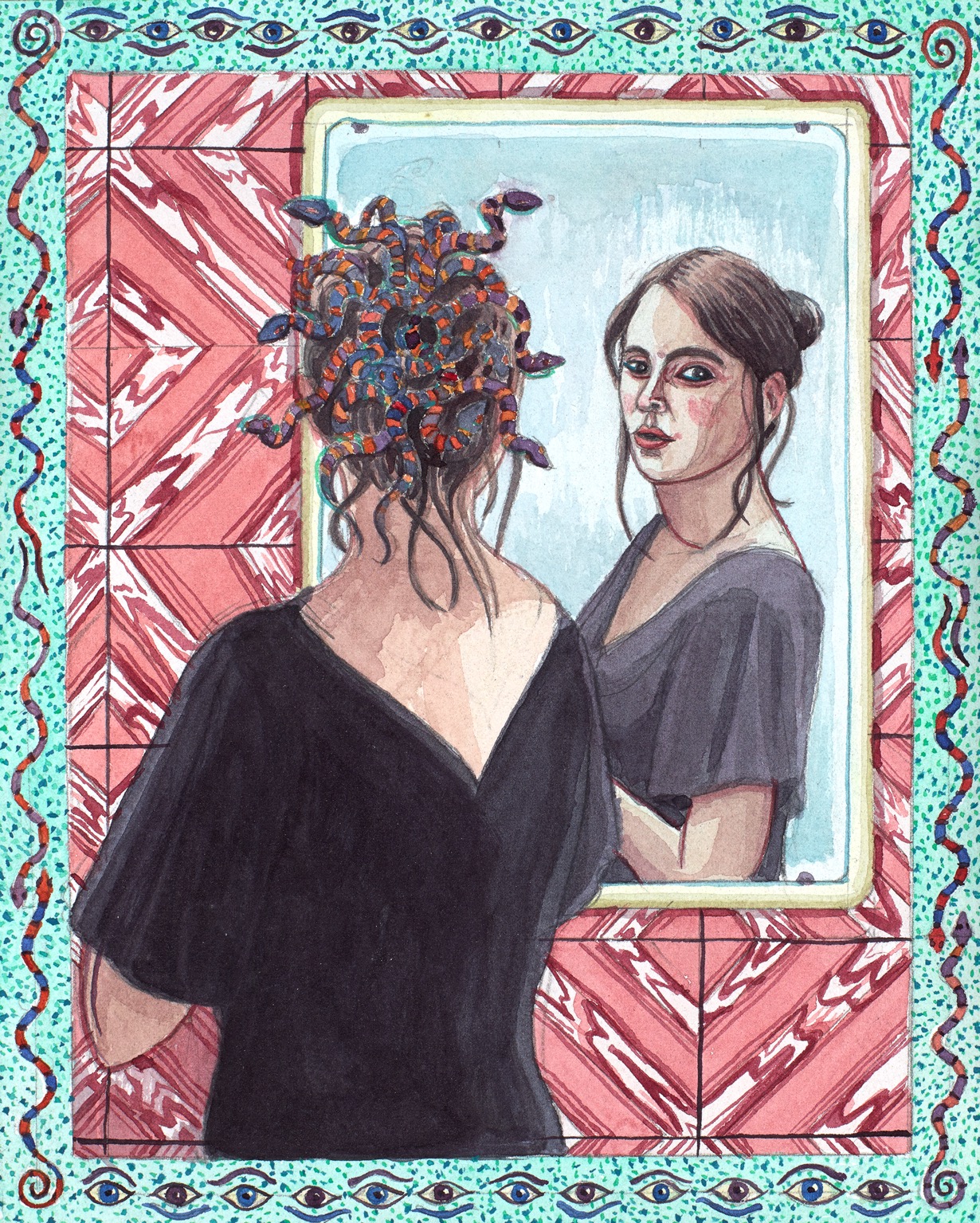

Study for “Medusa”

2018

Watercolor on paper

27 × 21 cm

Study for “Penthesilea”

2018

Watercolor on paper

22 × 26 cm

Text

The last two series of works by French-German artist Edouard Baribeaud (*1984) reflected his expeditions to enchanting, magical landscapes in India, which he had travelled extensively in 2016 and 2017. Such faraway landscapes of longing are merely hinted at in Baribeaud’s most recent group of paintings and watercolors, An Old Story for Our Modern Times (2018). Instead, we are drawn into puzzling interiors and encounter cryptic portraits – all deeply rooted in European art history and culture. And while Baribeaud no longer leads us through spectacular exteriors, these latest compositions have not lost any of their suspense and mystery. Indeed, having focused on the strange and foreign has enhanced Baribeaud’s perspective on the familiar. He refers to this shift as a process of rediscovery and re-mythologization. In one of the works the artist presents himself as the narrator of these fascinating stories: the watercolor Daedalus shows him somewhere between reality and fantasy, sitting at a custom-made work table he has designed himself to suit his needs – and which he has fittingly named All of Me.

Nearly all of these scenes can be traced back to Greek and Roman mythology. Baribeaud began the series with an empathetic portrait of Medusa: in her pinned-up hair, we discover a veritable knot of colorfully patterned snakes. However, the creatures cannot be seen in the mirror that she is gazing into. According to the myth, a glimpse of Medusa’s face would turn anyone into stone. The only safe way to look at her was via a mirror. So in Baribeaud’s pictorial version of the story, there is also no danger in the snake-free mirror image. Their simple, colorful shapes make the creatures look more like painterly ciphers than naturalistic rendering of a real threat. Ultimately, we perceive them as symbols of certain virtues. This corresponds with Baribeaud’s concept of Medusa as an image of our multi-faceted characteristics – contradictions included – and his intention to present her as representative of a modern woman. Narcissus, depicted as self-critical rather than self-regarding, is also composed as a figure of representation: shying away from any clear sexual attribution, thereby becoming a universal projection space.

Continue reading

One of the largest works in the exhibition features a contemporary version of Charon, the ferryman, who escorts the dead across the river to the entrance of Hades’ realm in exchange for an obol. In his rendering of the story, Baribeaud elegantly conveys the eternal wait of the dead, as well as the ferryman’s permanent state of waiting into a modern setting. Instead of the canonical image of a grim old man in a dark fisherman’s apron, the artist has placed a sexy young man in the smart entryway of a mid-century building. It remains unclear whether Baribeaud’s Charon is waiting for cargo or whether he is, indeed, waiting to gain entry into the netherworld himself.

In his Minotaur Baribeaud depicts a contrary form of masculinity. A male nude seems to transform into the man-eating creature while striding through a door. The next of Baribeaud’s mythical figures that we encounter is lasciviously lolling on wrinkled bed sheets: it is the Spartan princess Penelope, wife of Odysseus. During her husband’s two decades of absence, she cunningly puts off her many suitors, under the pretext that she could not respond to any advances until the shroud for her deceased father-in-law was finished. Every night, however, she unraveled her day’s work of weaving, enabling her to fend off the hopefuls while Odysseus wandered the world. This cloth, illustrating several episodes in the Odyssey, covers the protagonist. Like in the sweetly expressive Viennese Jugendstil compositions Baribeaud’s Penelope is shown in an expressive pose, set against an almost monochromatic background, whose deep blue alludes to the Odyssey. Baribeaud even picks up on the theme of the couple’s long separation in the embroidery of a moon cycle that frames the piece. With this delicate craftsmanship the artist – as is the case in Medusa – abrogates the distinct separation between the so-called fine arts and applied arts. This is also true for works like Daedalus and Danaë in which the artist applied gold leaf.

Baribeaud’s masterful fusion of ancient myths and references to modern art movements, such as Jugendstil or New Objectivity, culminates in his large-format painting Penthesilea. The protagonist succeeds in evading our gaze. She is in the process of getting changed, yet whether she is dressing or undressing remains unclear – as does the question of ownership of the conspicuously placed shirt in front of the folding screen. The screen is decorated with a scene from the so-called Amazonomachy – the mythical battle during the Trojan War between the Greeks and the Amazons, the female warriors. The painting that served Baribeaud as a starting point for this work is Henri Matisse’s The Pink Studio. Showing the light-flooded studio of the fauvist painter, The Pink Studio marked a change in perspective in its author’s career. The painting was done only a few years after Matisse left Paris and moved to a new home in the rural setting of Issy-les-Moulineaux. Here, art history would be written with the iconic painting The Dance. Even though the estate was just a few kilometers from Paris, the moderate change of location brought with it a new perspective on the seemingly familiar.

Through this combination of diverse references, Baribeaud has created a setting for Penthesilea that once again defies any clear assignment to a particular epoch. As in his other works, this approach allows him to create a stage populated with universal characters. In the case of this painting, the artist has lined up a cast of female types from a variety of eras and cultural contexts: there are the combative Amazons, the Virgin Mary, Matisse’s models, and the Hindu goddess of war. Even the second of the Matisse paintings Baribeaud cites, hanging on the left behind the screen, addresses the role of women in society – ironically through their absence, as it depicts only Muslim men. Baribeaud’s protagonist finds herself in the midst of these role models; in alluding to or rejecting these stereotypes, she is forced to carve out a genuine understanding of herself. The considerably smaller but equally colorful The Navel of the World is a variation of this composition.

Baribeaud’s new paintings and watercolors are not contemporary illustrations of Greek and Roman myths. Instead, the artist uses these traditional narratives to create projection surfaces and effective stages, upon which he assembles a cast of contemporary figures who experience human dramas that have remained unchanged for millennia. All these works are about multifaceted characters, relationships, and the individual’s place in society. They are about loneliness, life, and death. The basic heroic stories may be ancient, but the drama could not be more contemporary.

Catalogue

Edited by

Juerg Judin, Pay Matthis Karstens and Ashwin Thadani

Texts by Imran Ali Khan, Sabine Thümmler and Pay Matthis Karstens

In German and English

255 × 314 mm

123 pages, hardcover

62 color ill.

Published by Hatje Cantz, Berlin 2018

ISBN 978-3-7757-4454-6