Edouard Baribeaud

The Hour of the Gods

Works

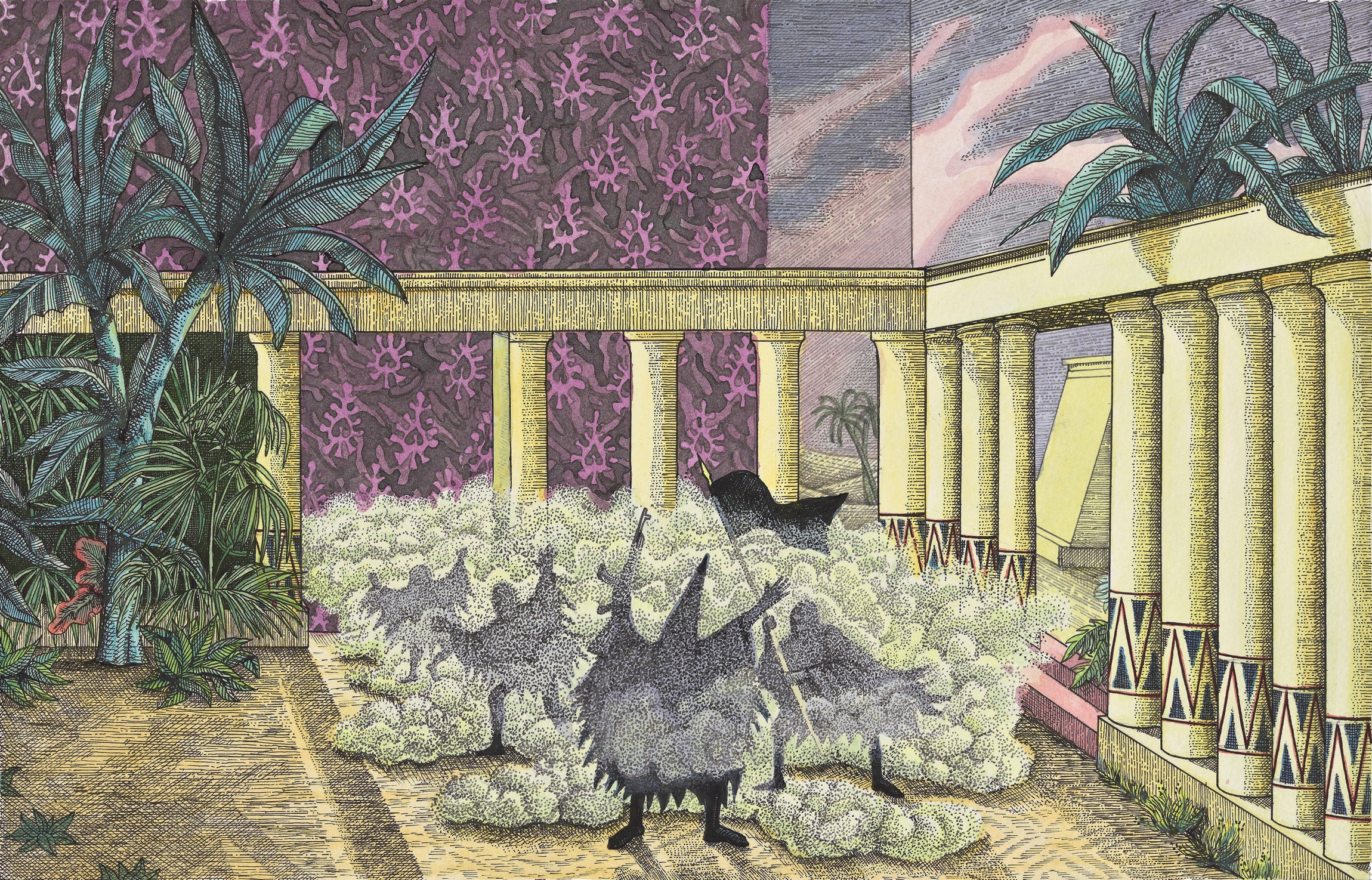

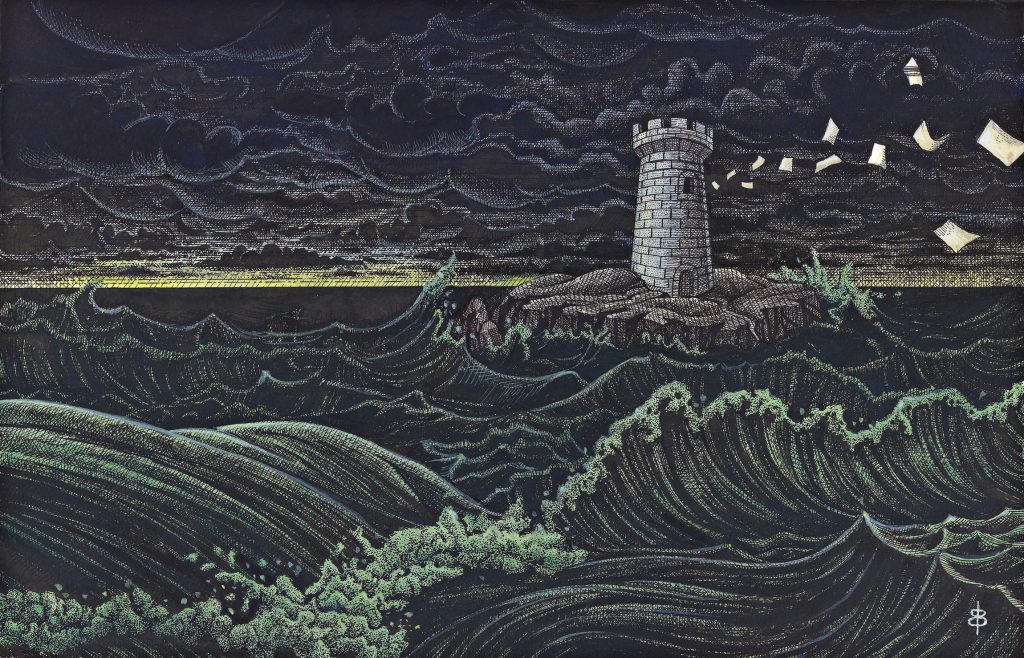

Tis the Djinns’ Wild Streaming Swarm

2015

India ink and watercolor on paper

29.5 × 46 cm

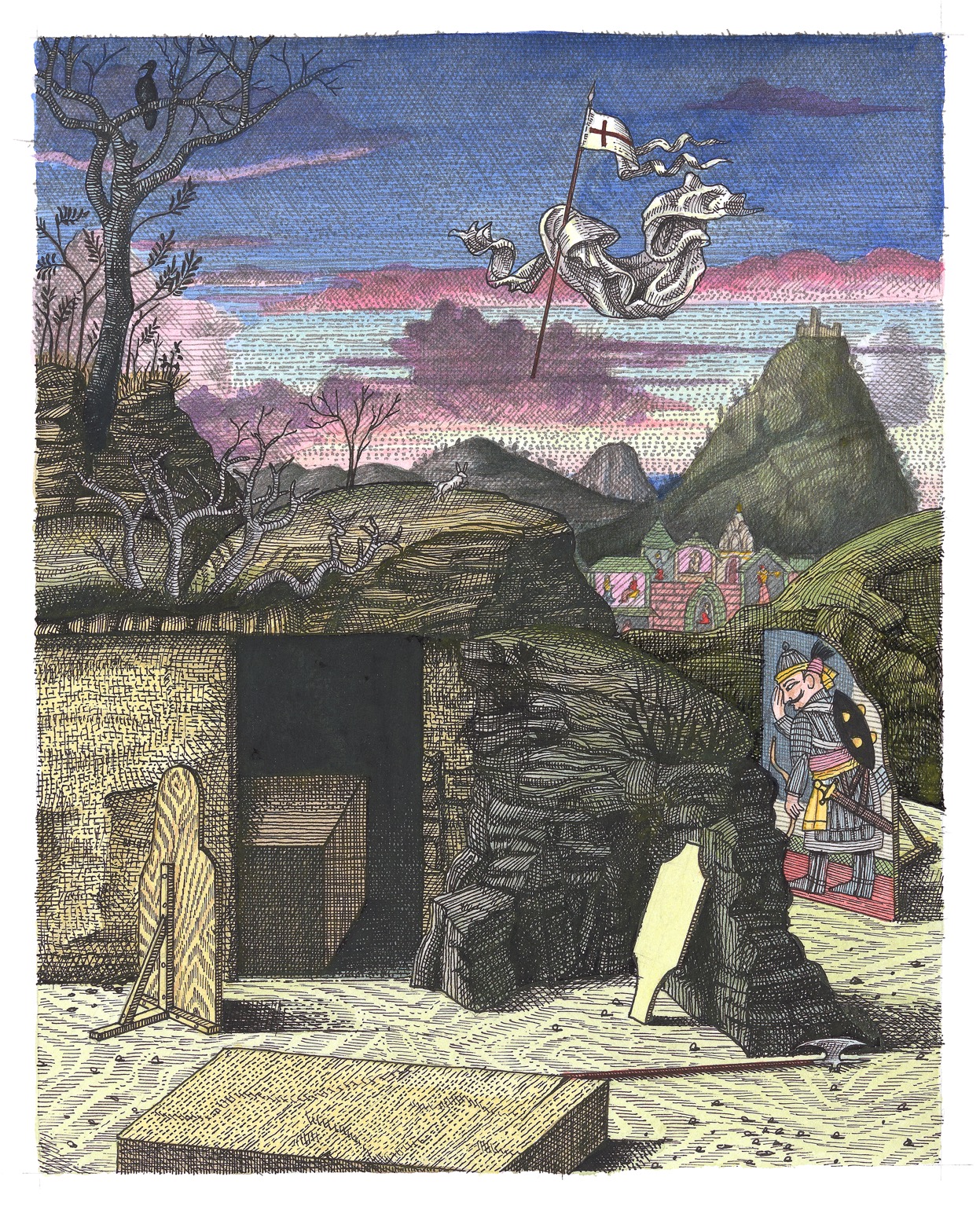

The Mystery of Faith

2015

India ink and watercolor on paper

29.5 × 23.5 cm

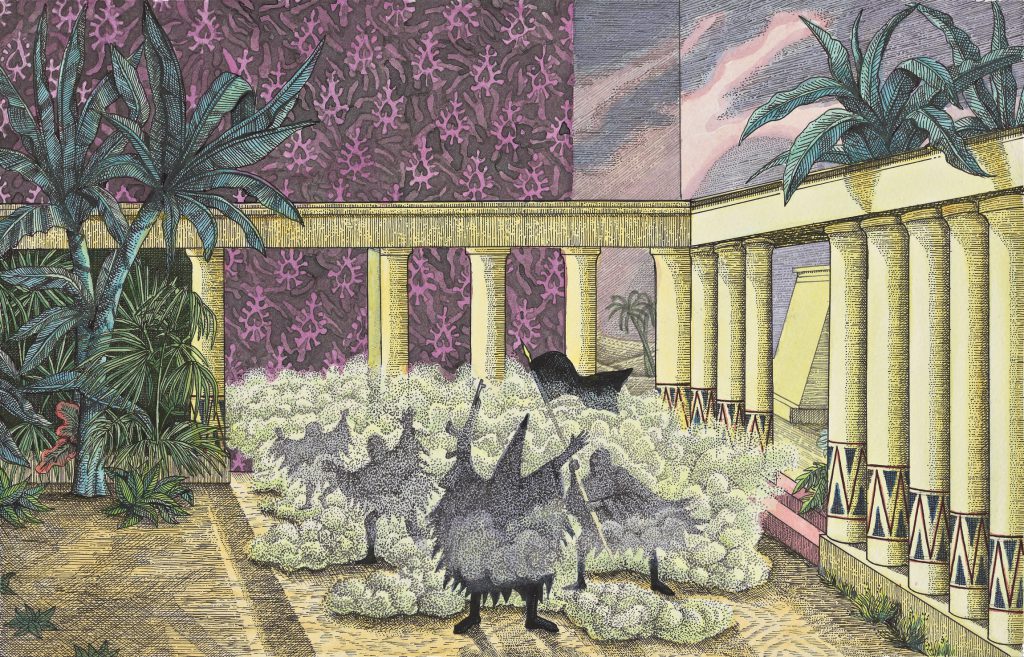

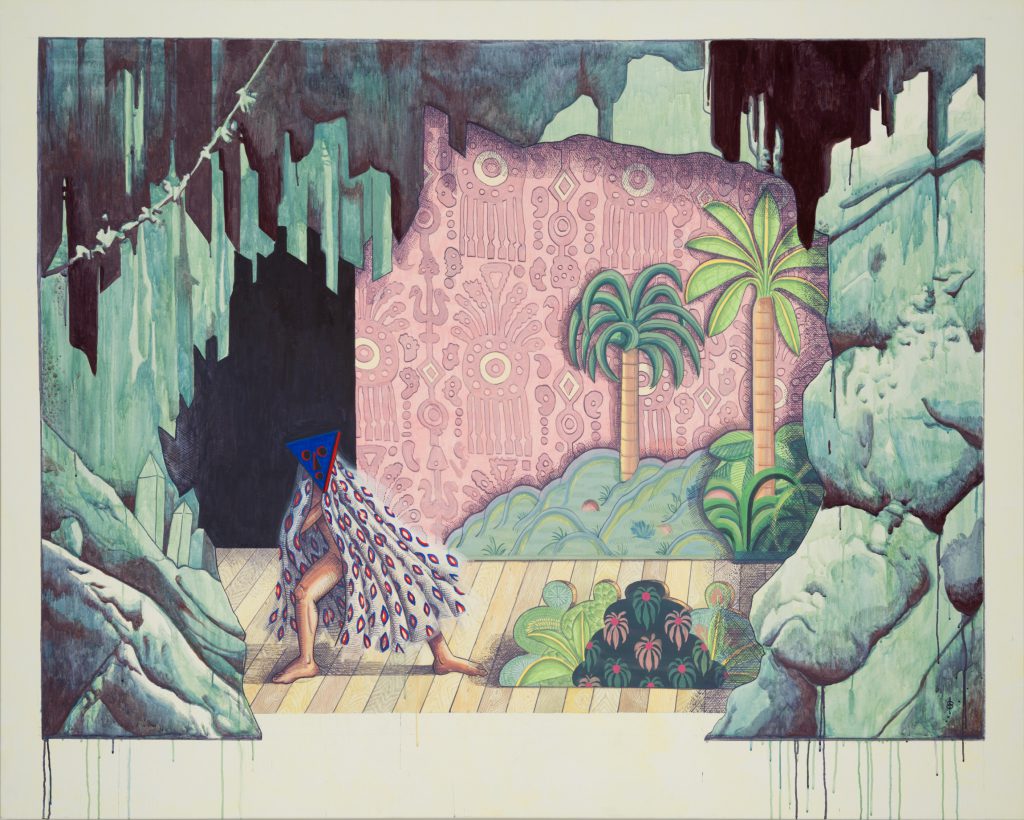

La danse du sauvage

2015

Egg tempera on canvas

160 × 200 cm

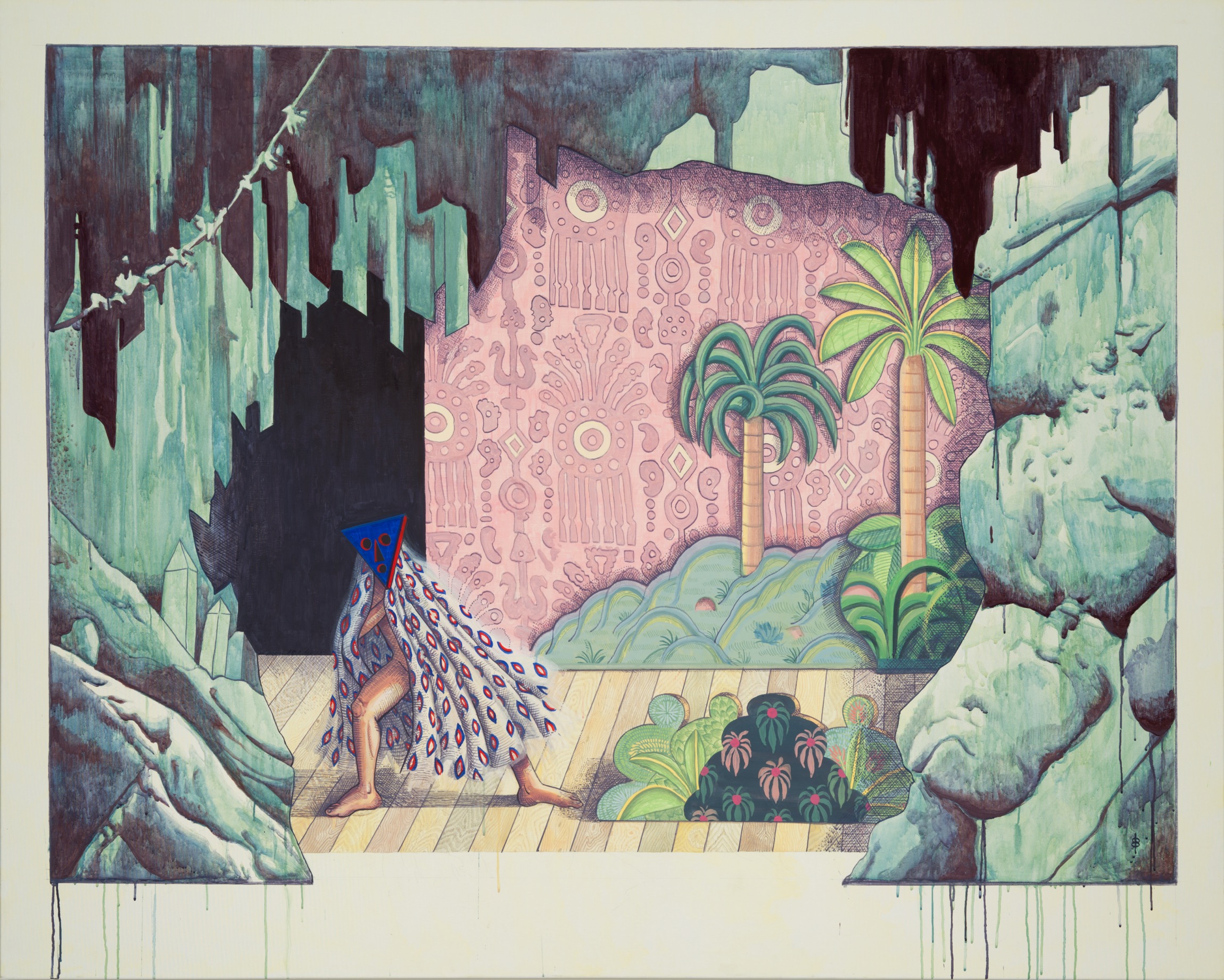

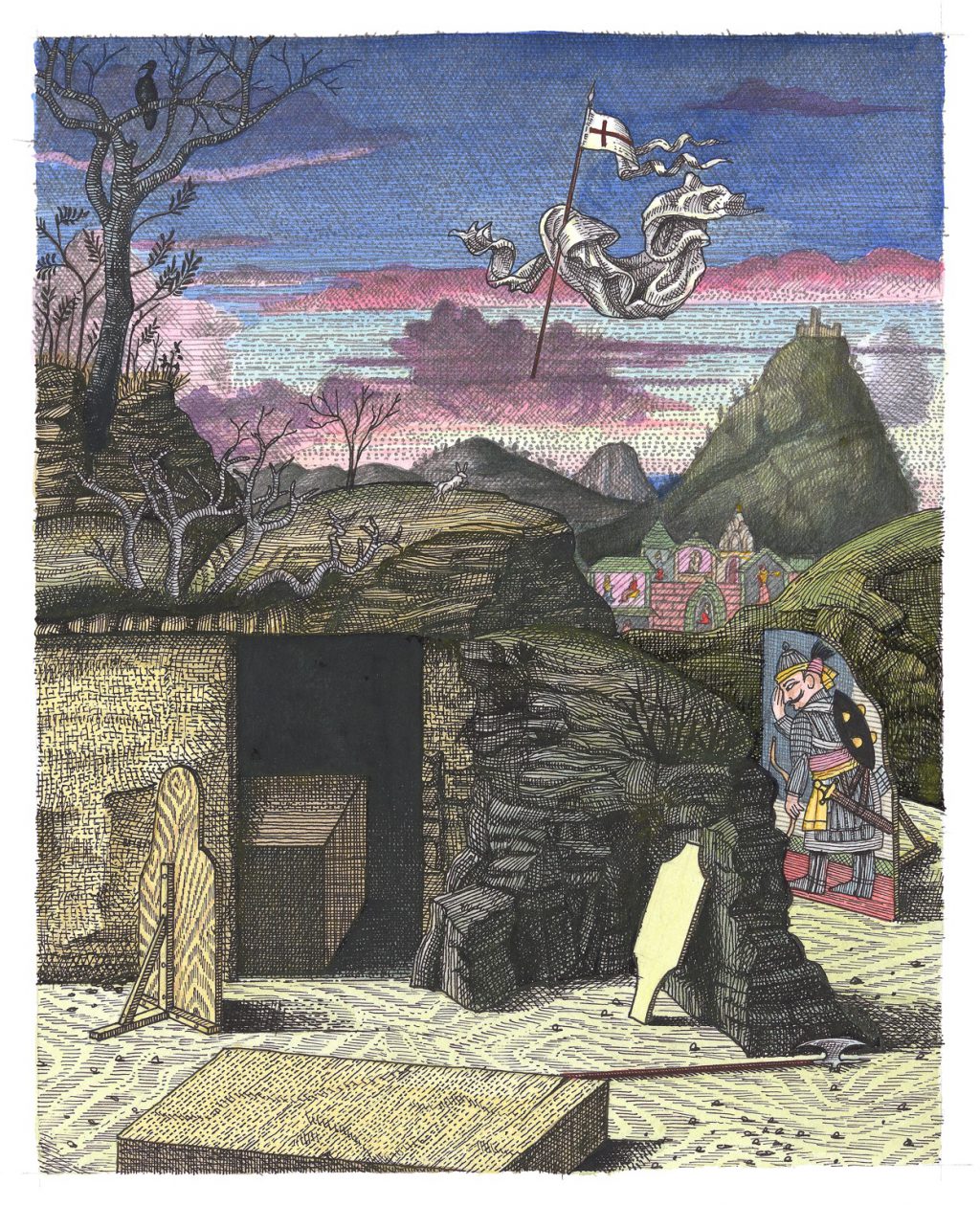

Kathputli’s Dream

2015

India ink and watercolor on paper

28.5 × 22.5 cm

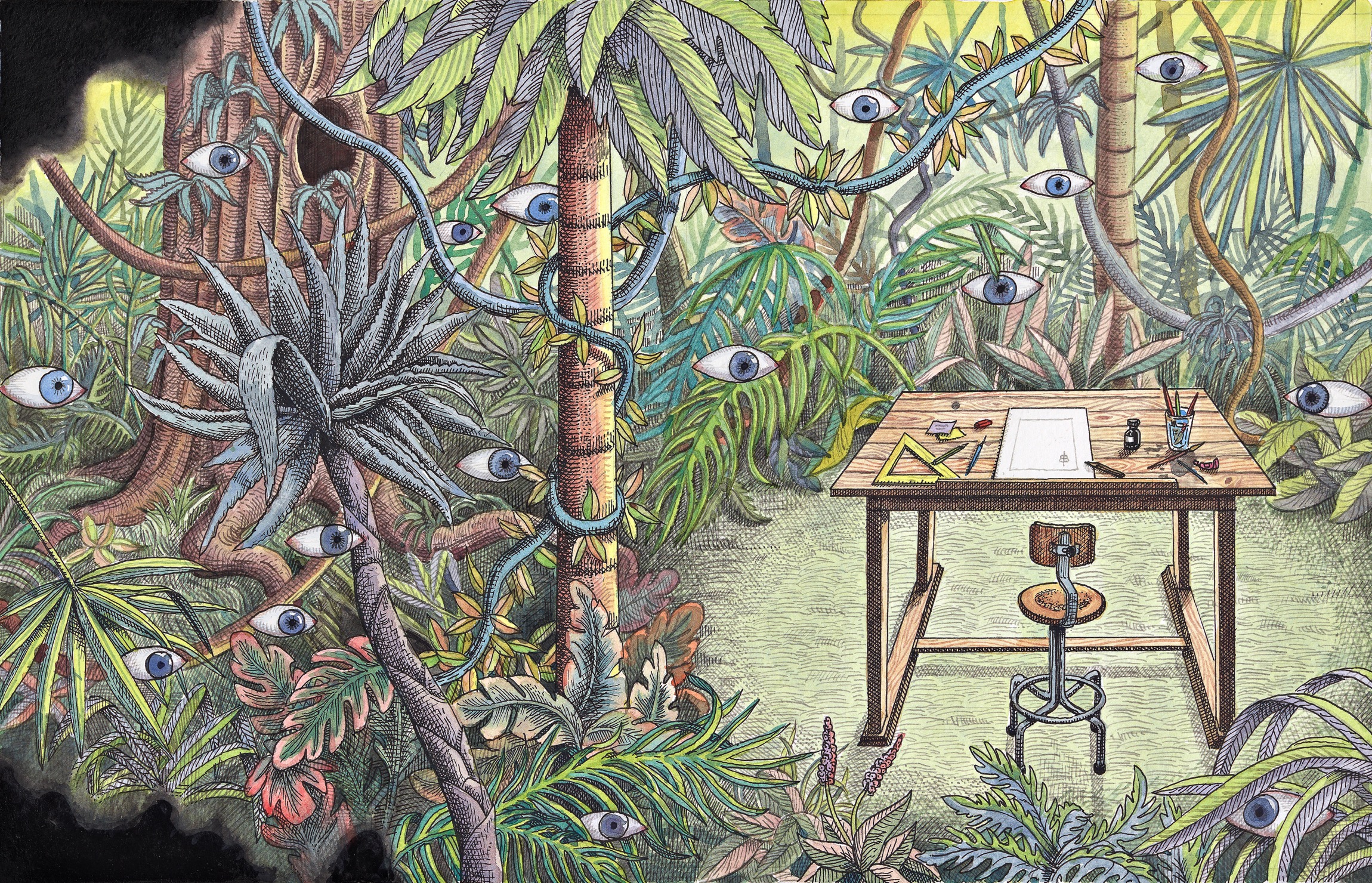

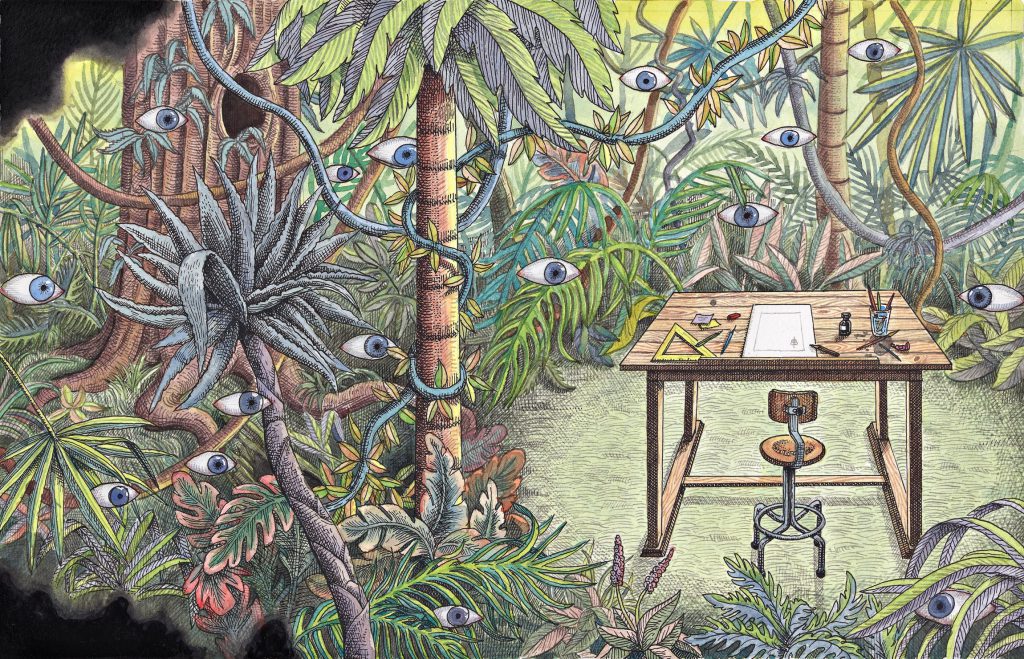

Drawing Through the Jungle

2015

India ink and watercolor on paper

29.5 × 45.5 cm

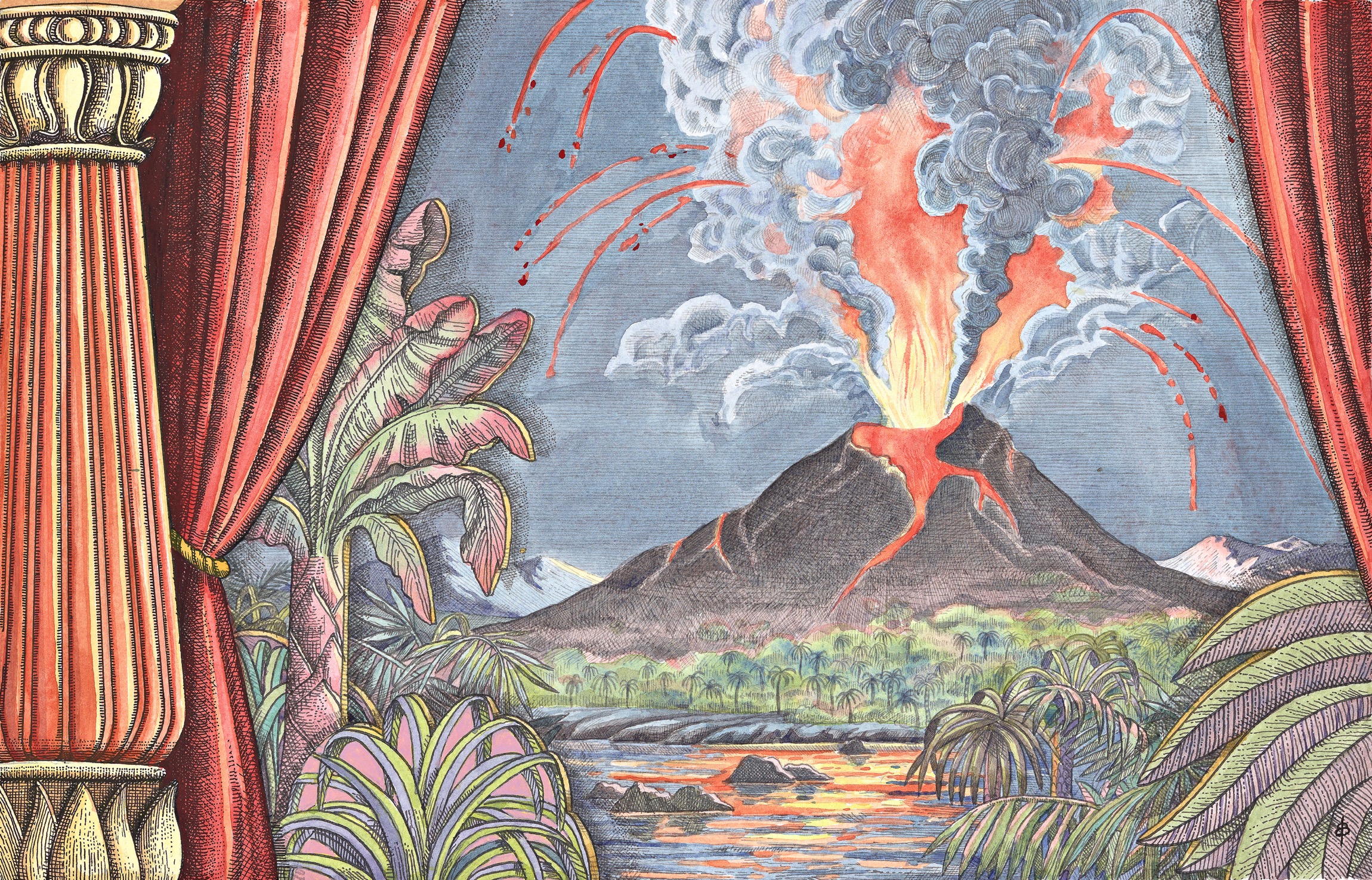

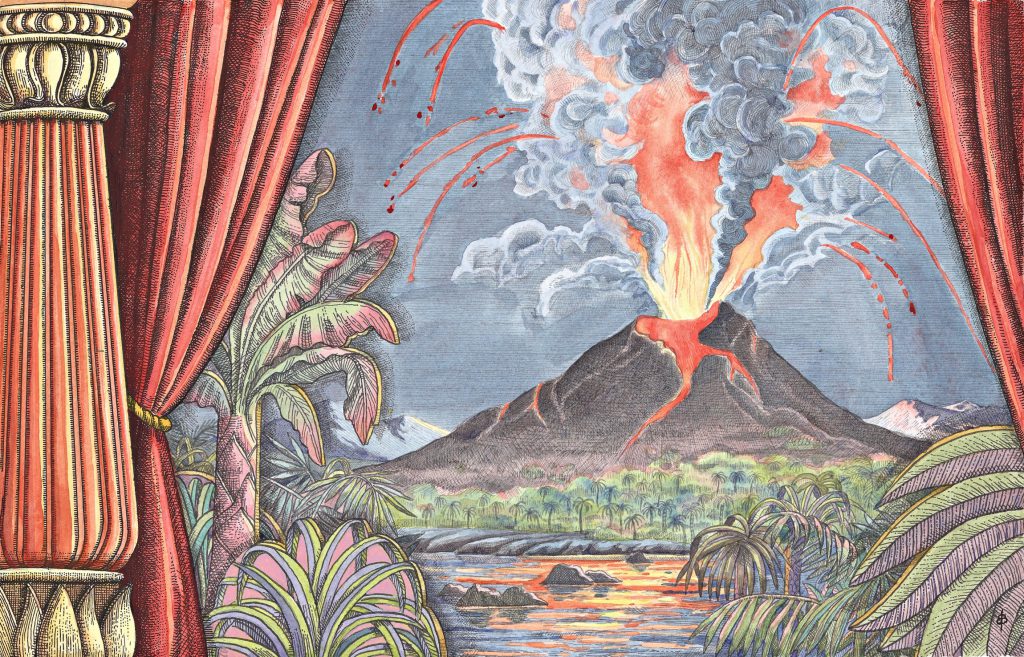

Empedocles at Mount Semuru

2015

India ink and watercolor on paper

29.5 × 46 cm

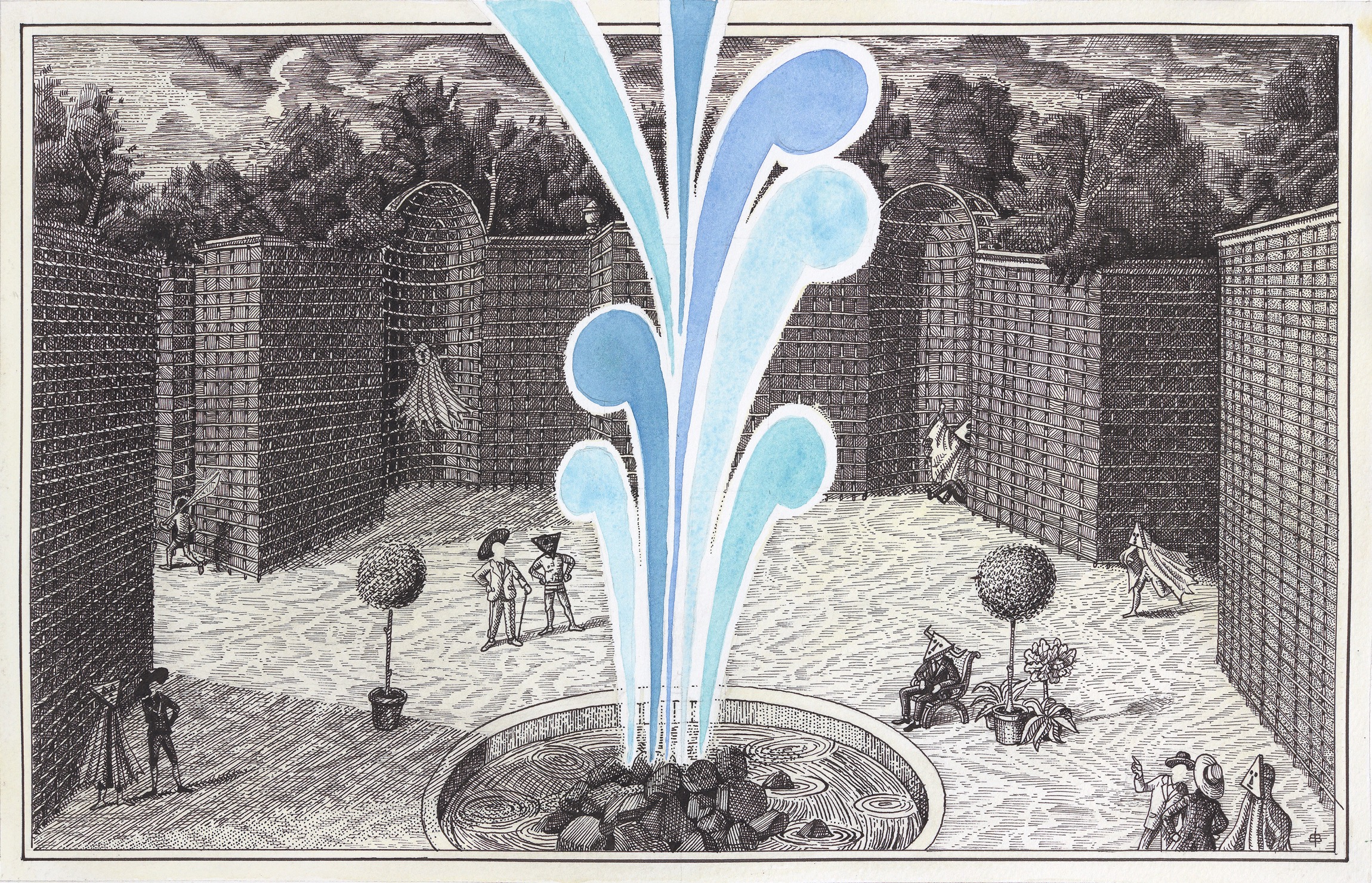

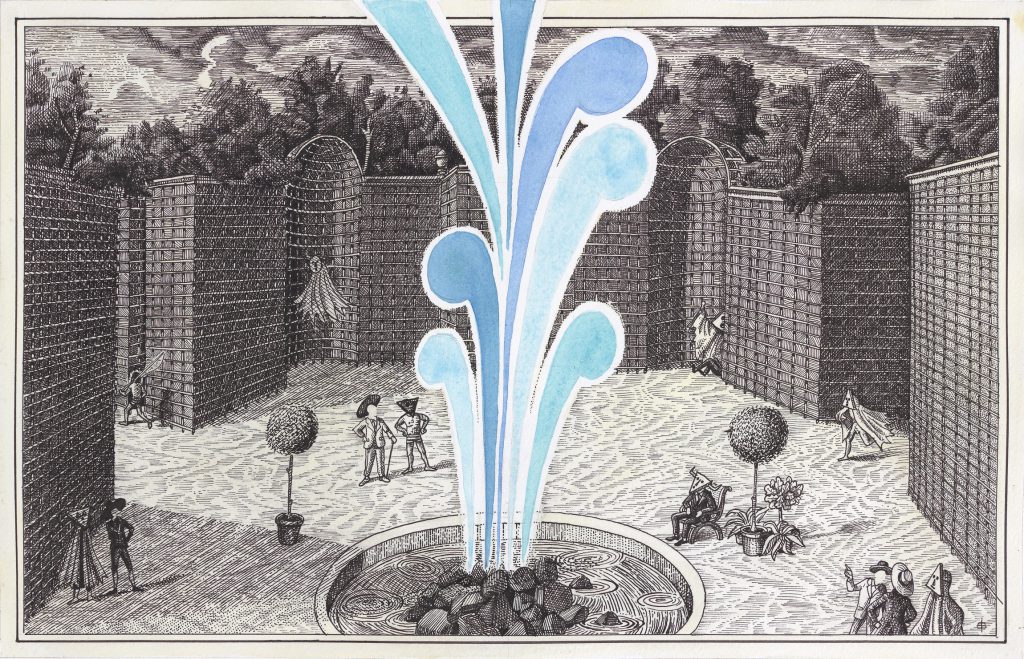

Gnossiennes

2015

India ink and watercolor on paper

29.5 × 46 cm

The Fall

2015

Egg tempera on canvas

160 × 200 cm

Hanuman

2015

Egg tempera on canvas

160 × 200 cm

The Storm

2015

India ink and watercolor on paper

29.5 × 46 cm

Text

Edouard Baribeaud collapses reality and imagination onto each other in his work, creating scenes that, though static, appear as if, with the gentlest prod, they might animate and carry forth a vibrant, fantastical narrative. Monkeys, tropical birds, and trees tumble through the air. A grand stage curtain is withdrawn to reveal the eruption of a catastrophically large volcano. A masked man, part hero, part shaman, dances across an imagined stage. Papers fly from a single ocean-bound turret caught in the midst of a tempest.

In The Hour of the Gods, Baribeaud’s second solo exhibition with Galerie Judin, the French-German artist presents a new series of work, all created in 2015. The title of the show refers to the twilight hour of day known in India as “godhuli bela” (literally translated: “the time of cow dust”) – when dust rises from the hooves of cattle returning to their village at sunset. As the evening shadows begin to lengthen, people and animals all head back to their homes to rest. It is the sacred time when Lord Krishna brought his own cattle safely home. The exhibited watercolors and paintings were inspired by a trip to India that Baribeaud undertook in November and December of 2014, as part of an ongoing film project.

Taken particularly by the tradition of Indian miniature painting, Baribeaud began to appropriate elements and the style within the drawings and paintings now on view at the gallery. Compositional elements such as the red frame that borders Le déclin and The Fall but also The Mouth of the Cow hint at this genesis point for the works as does the graphic nature of the vegetation present throughout the works on view. Particularly in Popol Vuh‘s Garden and La fuite du sauvage plant life is rendered in a manner redolent of textile patterning or woodblock printing, both tying the work to its art historical basis in the Indian tradition and suggesting that, though representational, realism remains an arm’s-length concern in the works – much closer are myth and parable.

Continue reading

Centrally at stake within The Hour of the Gods is a contemporary reassessment of Orientalism, the 19th century art historical moment, which saw academies across Europe cast their gaze on the Middle East, and was later solidified into theoretical discourse by Edward Said’s 1978 book of the same name, which took up the reductive (and to a great degree imagined) nature of those paintings and other representations of the East by the West as a means of asserting a perception of Western society’s superiority over the Eastern Other. Baribeaud, who in a previous series Hic sunt leones (2011/2012) explored notions of home particularly with regard to his dual heritage, took to the Orientalist tradition to examine to what extent his preconceived notions of the East and India in particular might influence the way in which he would represent elements encountered on his journey.

The exhibition marks two major developments in Baribeaud’s practice, debuting both his first series of paintings on canvas and his first major installation. The paintings hold steadfast to the artist’s roots as an illustrator and print maker, having studied at Paris’s prestigious École nationale supérieure des Arts Décoratifs. Accustomed to creating large-scale works in gouache on paper, Baribeaud turned to the ancient and technically challenging medium of egg tempera for his canvas-based works. Largely outmoded since the invention of oil paint in the 16th century, the technique gives a flatness to the image surface and leaves the works devoid of oil painting’s weighty materiality. It also allows Baribeaud to approach painting with the same image-making logic he honed in etching, silk screen, and lithography – notably, opposite from that typically used by oil painters – which sees him start from the lightest element in the works (always the inherent color of the paper or canvas) and work progressively darker.

For The Devine Wrath, the space-filling installation at the centre of this exhibition, Baribeaud invites the viewer to enter one of his imagined scenes. The volcano motif from Empedocles at Mount Semuru is recreated within the space using a series of cut-out structures, which provide the rudimentary approximation of perspective most often seen in a budget theater set. Whereas the artist’s two-dimensional work remains static, this space is activated by each individual who passes through, becoming a temporary character in the life-scale set.

The installation’s reference to the theater exposes further elements of Baribeaud’s works on paper and paintings. Take Kathputli’s Dream, for the most explicit instance of this theme, courtesy of a puppet theater placed within a thick, dream-like forest. The piece references Baribeaud’s continued interest in the tradition of Kathputli marionette puppetry in the Indian sub-continent, what is also the subject of his forthcoming film.

Examining Baribeaud’s puppet theater more closely, the viewer begins to identify elements of representation within it – and for that matter, The Devine Wrath – from the artist’s other works on view. Gnossiennes reveals itself as an elaborate set, a masked man entering stage left while a vagabond exits stage right. The residential structure in the distance of The Mouth of the Cow and Day after Day appears, on closer inspection, to be a shoddily constructed set piece or hand-rendered theater backdrop. Throughout the works on view, vertical elements reveal themselves to be as if cardboard approximations of the real thing.

For Baribeaud, the Indian puppet theater is much more than a mere aesthetic device. The thousand-year-old tradition is characterized by its place within Rajasthani culture as both a means of entertainment, but more importantly as a conduit for education and social commentary. Baribeaud pulls from a wealth of cultural bases for the “theaters” in the works on view. The story of Hindu god Hanuman lifting a Himalayan mountain to bring a life-giving herb to a wounded Lakshmana is represented by the toppling trees and tumbling monkeys of Hanuman and The Lifting of the Sacred Mountain. Icarus’s fall into the sea from his waxen chariot is represented in Le Déclin and The Fall – his plunge suspended as if by a stage rope with feathers floating past the fourth wall and out of view. A band of Djinn, supernatural creatures of Muslim mythology, skulk forward into view in the Victor Hugo inspired ‘Tis the Djinns’ wild streaming swarm.

Other recurring figures in the works on view, such as the triangular-masked man that crops up numerous times in The Hour of the Gods are less explicit in their identity. To the uninitiated viewer, he might be a spirit, a knight, a bandit, or indeed a man in costume. Many of the figures, and indeed much of the series as a whole, were initially inspired by Jean Philippe Rameau’s 1735 ballet héroïque “Les Indes galantes”, in particular the ballet’s final act “Les sauvages” (The Savages), a touchstone moment in the Orientalist tradition.

Equal parts tumult, fantasy, and wit, Baribeaud’s works enliven their viewer, offering an escape from day to day concerns and a tableau on which to unfold more sublimated sections of the mind.