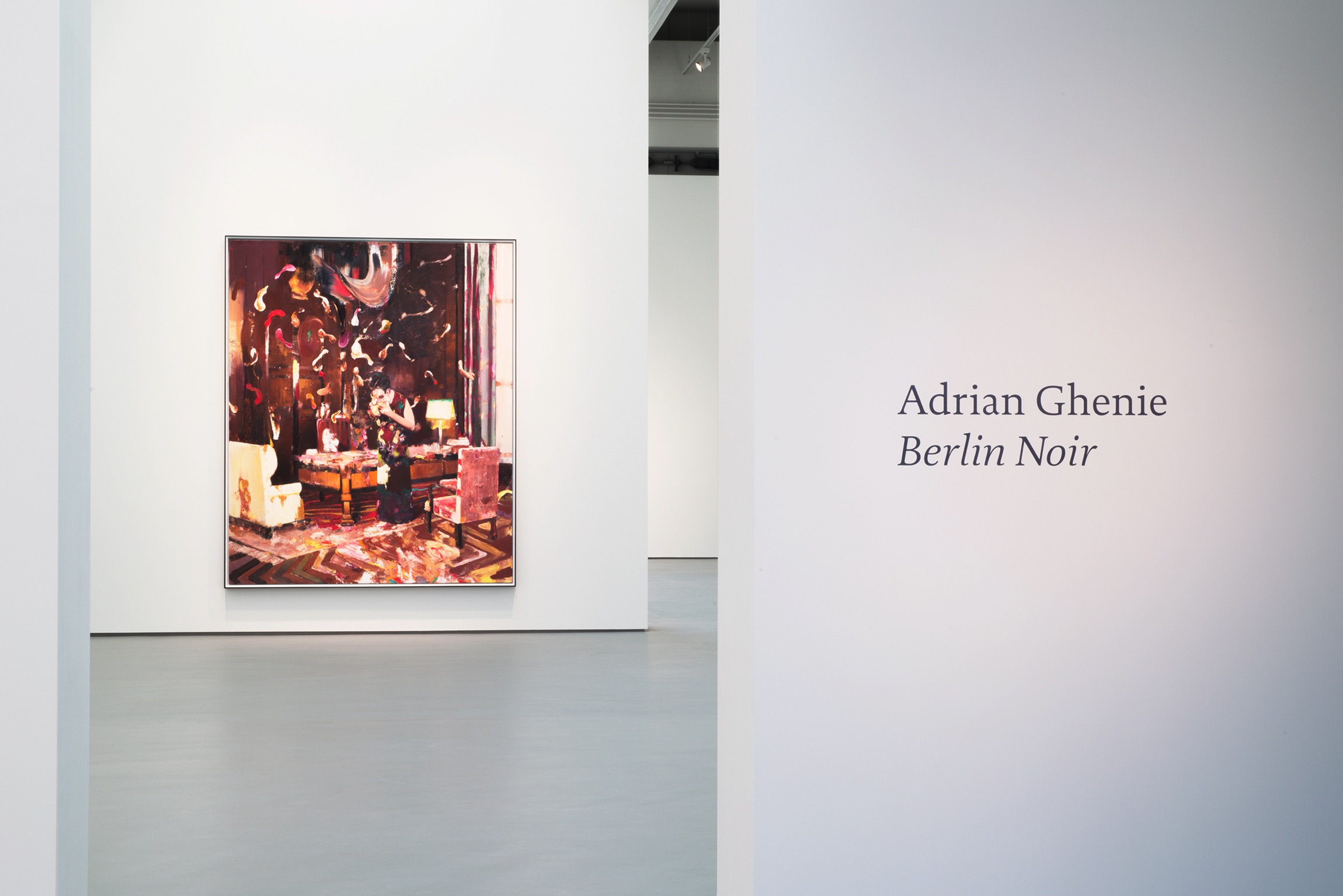

Adrian Ghenie

Berlin Noir

Works

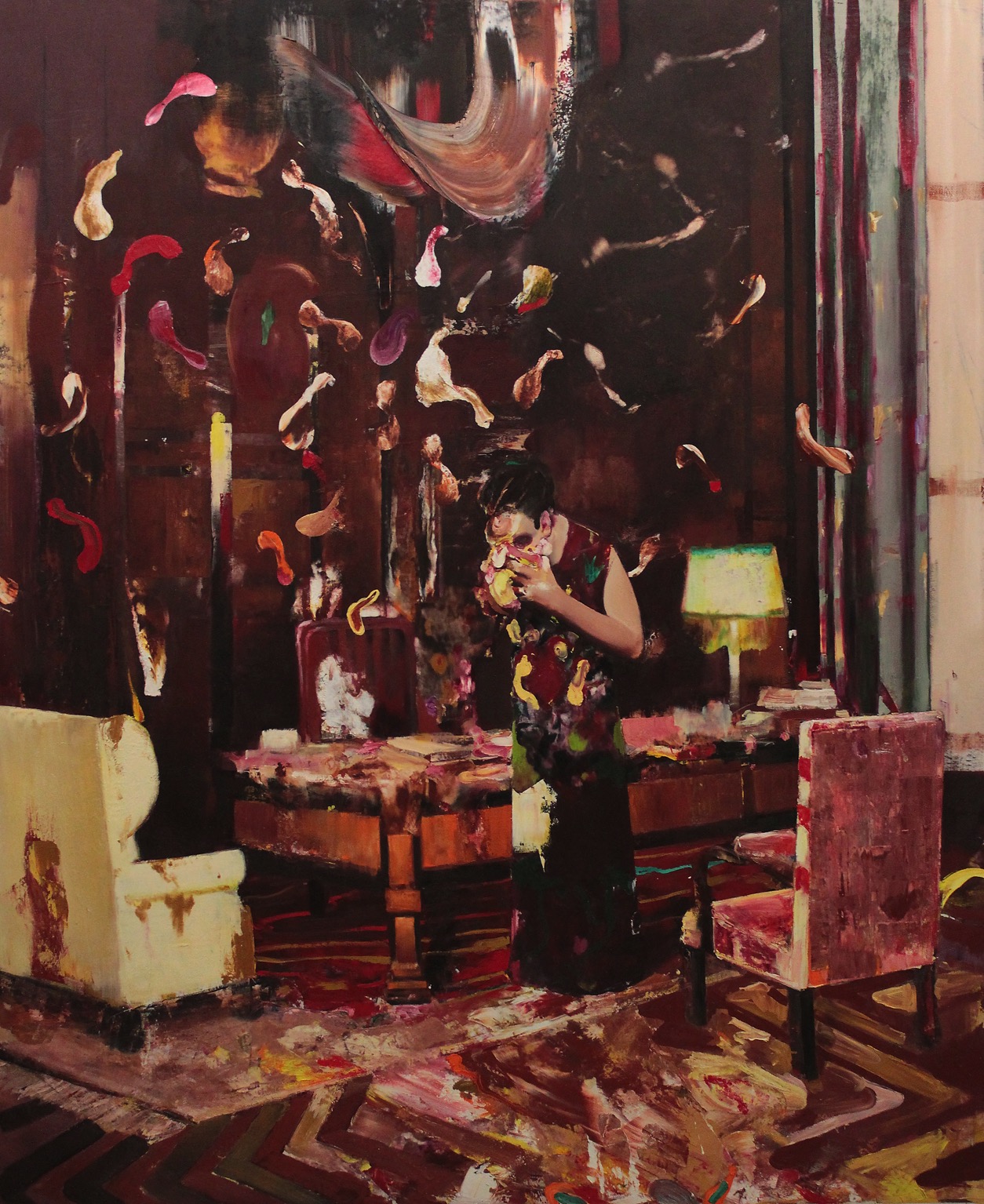

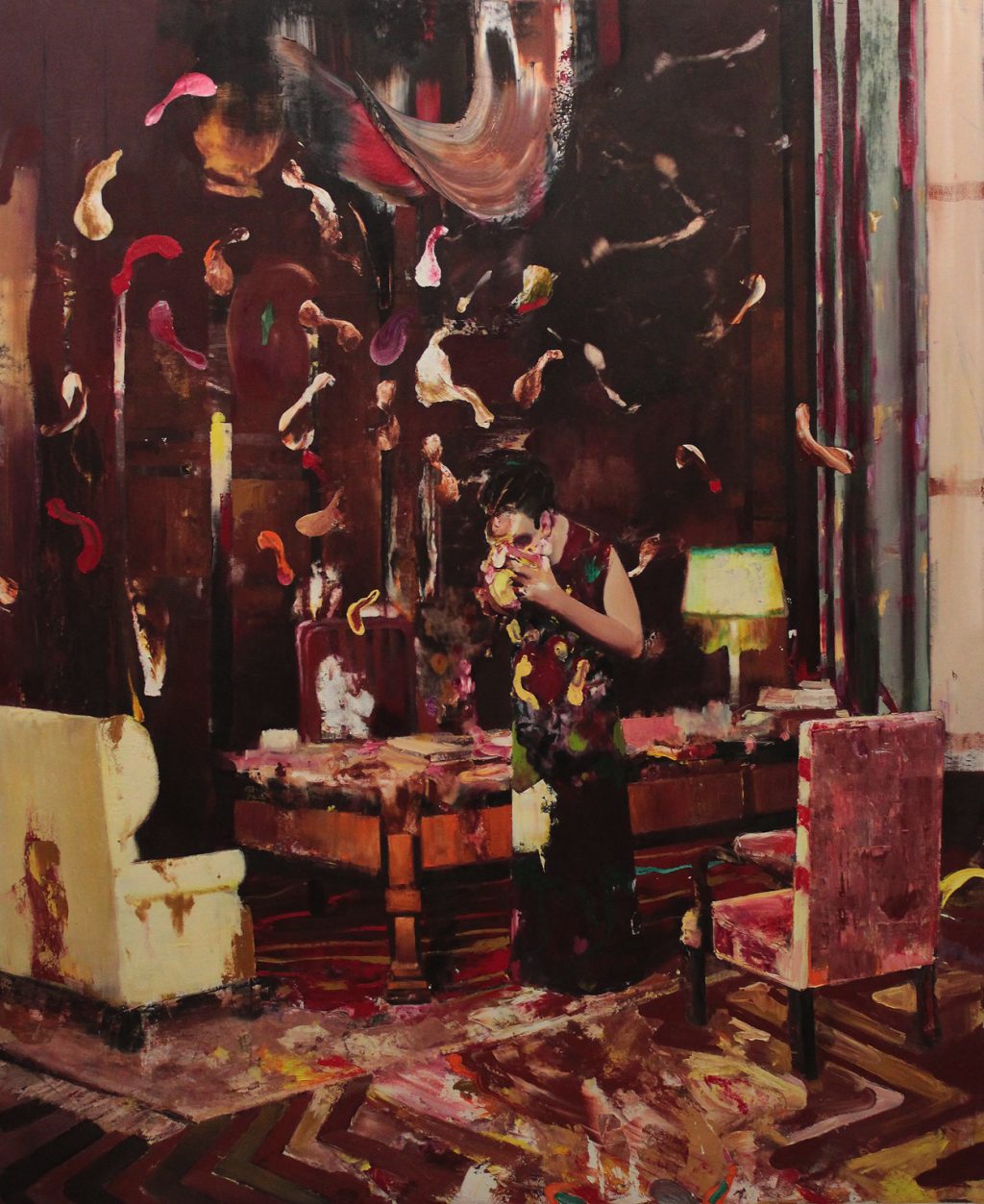

Pie Fight Interior 11

2014

Oil on canvas

280 × 230 cm

Opernplatz

2014

Oil on canvas

130 × 100 cm

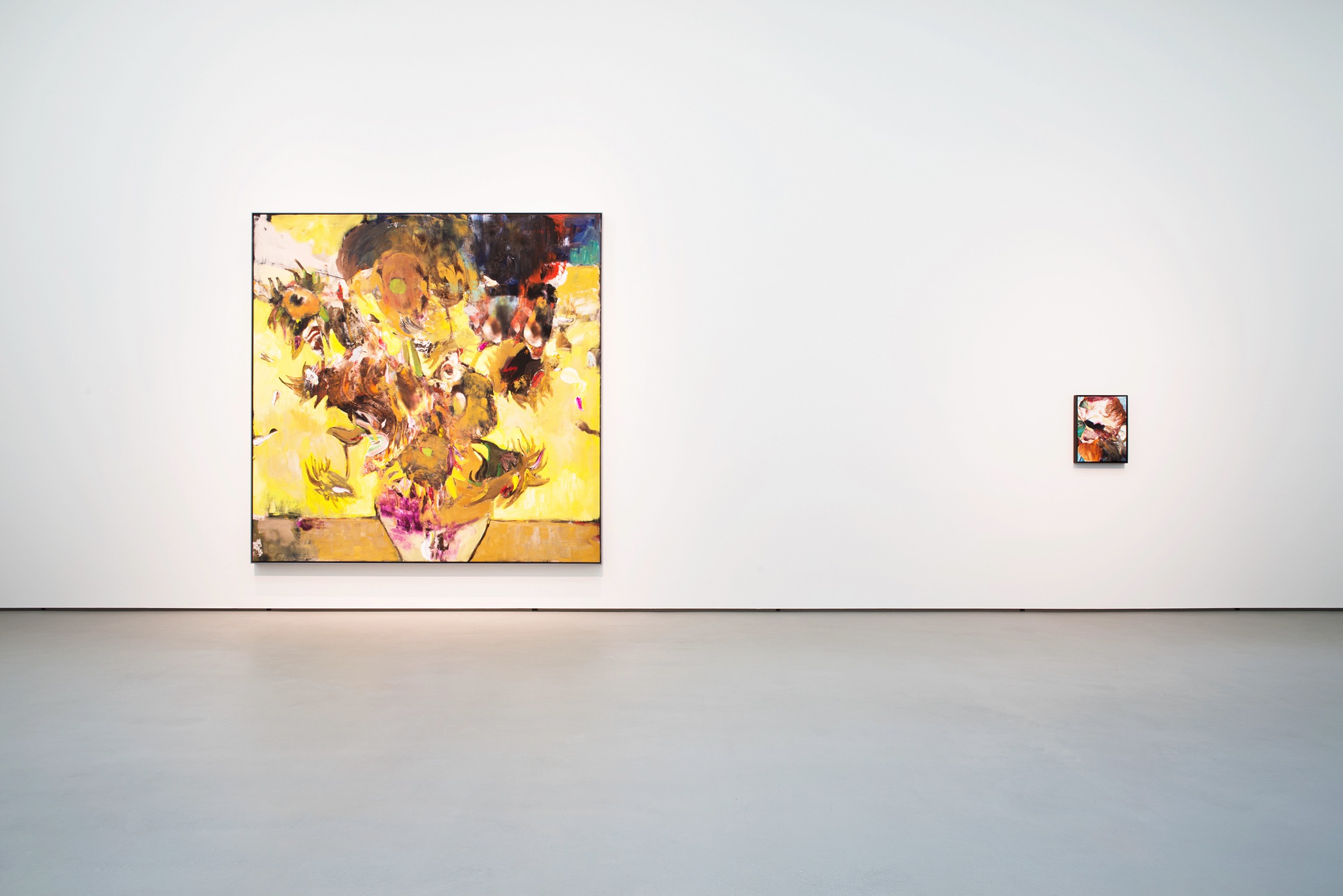

The Sunflowers in 1937

2014

Oil on canvas

280 × 280 cm

The Arrival

2014

Oil on canvas

210 × 165 cm

Degenerate Art

2014

Oil on canvas

53 × 40 cm

Pie Fight Interior 13

2014

Oil on canvas

54 × 45 cm

Pie Fight Study

2014

Oil on canvas

74 × 55 cm

Burning Books

2014

Oil on canvas

57 × 60 cm

Carnivorous Flowers

2014

Oil on canvas

42 × 52 cm

Text

Berlin Noir, the title of Adrian Ghenie’s third solo exhibition at Gallery Judin, is a reference to British author Philip Kerr’s popular trilogy of crime novels, in which his protagonist Bernhard Gunther, a private eye in 1930’s Berlin, plumbs the uncharted abysses of the human soul. And indeed, in some of the works in this exhibition – consisting of nine paintings and one large-format work on paper – we encounter the sinister schemes of the Nazis and their henchmen. Other works seem to, at least at first glance, have stumbled into the wrong century. The choice of motifs for the exhibition appears to be, mildly put, extremely heterogeneous. But those who have followed Ghenie’s breathtaking development since his first exhibitions in 2006 are unlikely to be confused by this tactic of telling stories through history, and from unexpected perspectives.

Berlin plays a special role in Adrian Ghenie’s life. In 2011 he finally made this city his home, both personally and professionally, after having worked here on and off for the last several years. Unlike many other artists, who appreciate Berlin for its low costs of living and the all-pervasive sense of excitement and innovation, Ghenie is attracted to its past. He calls it “the extra layer that this city has”, by which he is referring not only to its historicity and the visible traces of a century that brought this city, more than any other, its greatest triumphs and the most unfathomable suffering imaginable. Coming from Eastern Europe, he feels that Germans “understand” him, feels some kind of kinship rooted in a shared experience of dictatorship and a sense of collective tragedy. Most of all, Ghenie is fascinated by the fact that Germany, alone among the great centers of western culture had once renounced civilization, and instead turned to a modern form of barbarism. A people that at one time had produced painters such as Dürer and Friedrich, in the 20th century Germans were eliminating parts of the museum collections, and university professors were encouraging their students to burn books by Kästner, Freud and Tucholsky.

Continue reading

The images of those ecstatic students chanting their songs in the eerie glow of the pyres of burning books on the square in front of Berlin’s Humboldt University, are the point of departure for Ghenie’s engagement with this original sin of German cultural history. The painting Opernplatz (2014 – like all the paintings in the exhibition) shows a bird’s eye view of what is today Bebelplatz, surrounded by the Staatsoper, University and St. Hedwig’s Cathedral. It is not, however, the book-burning that dominates the painting’s composition, but rather a dramatic sky with storm clouds and an overcast full moon. On the evening of the 10th of May 1933, it was pelting down rain in Berlin, such that the piled-up books could not be set ablaze but with the help of petrol. There was thus no celestial help in this “fight against all that is Un-German”, and this is what Ghenie might have had in mind when he painted this sky. The composition is reminiscent of the famous “Alexanderschlacht” (1592) by German renaissance Master Albrecht Altdorfer, in whose dramatic sky a rising sun symbolizes the just triumph of the (good) Greeks over the (barbaric) Persians. In an inverted paraphrase thereof, the bleak moon over the Opernplatz is shining a light on a new breed of barbarians.

The much smaller Burning Books describes the same event from the more conventional perspective of an eye-witness. Faceless onlookers are standing around the fire, burning paper swirling through the air. It is one of those moments in history that have, by way of black-and-white photography, indelibly etched themselves into our collective memories. Rendering this barbarous act in color, the artist becomes capable of stripping away the soothing sense of temporal distance, thus giving the event an almost contemporary character.

Less famous than the public burning of “Un-German literature” is the destruction of those pieces of “degenerate art” that could not be sold off on international markets, which took place on the 20th of March 1939 in the yard of the fire station Lindenstraße in Berlin-Kreuzberg. Estimates vary between sources, but it is safe to assume that some 20.000 works of art were destroyed. For a painter, this is of course an even more unbearable thought than the burning of books, given the fact that most of them were irreplaceable originals. Vincent Van Gogh, at the beginning of the 1930s already well-represented in Germany’s private and public collections, was also designated a “degenerate” artist, but luckily his paintings were already very valuable, and could thus escape destruction. For the small-format portrait of Van Gogh, Degenerate Art, Ghenie once again draws on his collage-technique, in order to achieve a deconstructivist composition of the image. The face is literally composed of animal parts – bits of fur, fish bellies, flaps of skin – as is clearly visible in studies for this painting. The painted version only hints at them. Van Gogh plays a key role in Ghenie’s biography. One of his sunflower paintings graced the cover of a Romanian art magazine, which fell into the hands of the then six-year-old, and then spent the next few months under his pillow. The grown-up artist‘s first encounter with the famous self-portrait in the Musée d’Orsay was a crucial experience: Van Gogh’s unusually cold and piercing gaze, with which he fixes upon the viewer, deeply disturbed Ghenie. It was only several years later that he saw the Nazi-Thriller “The Night of the Generals”, where the d’Orsay self-portrait makes Peter O’Toole nauseous when he looks at it in a Parisian depot for stolen art. For Ghenie, however, van Gogh’s critical, penetrating gaze is not directed at the viewer – but rather, at himself.

Ghenie has already engaged with this issue in a series of paintings, such as Self-Portrait as Vincent Van Gogh (2012 – not in our exhibition). His very best ideas are always the result of an interweaving of general (art) history with his own biography. A highlight of this exhibition – the monumental The Sunflowers in 1937 – is no exception here. It is based on the famous series of sunflowers in a vase that Van Gogh painted between 1888 and 1889 in Arles. They were for him a symbol of joy, warmth and friendship, and were intended as decoration of the joint “Studio of the South” that Van Gogh hoped to share with Paul Gauguin. As we know, this project flopped spectacularly, costing Van Gogh an earlobe. In Ghenie’s painting, the flowers seem to singe, to dissolve. In fact, he did consider how precisely flames would attack the surface of an oil painting, what chemical and physical processes would be triggered. One of the seven versions of Van Gogh’s sunflower paintings fell victim to the flames in Japan during World War II. Another magnificent version now hangs in Munich’s Neue Pinakothek – only a stone’s throw from the place, where in 1937 the show “Degenerate Art” was put on in order to mock masterworks of Impressionism, Expressionism and modernity in general. Just as Dorian Gray’s painted likeness ages prematurely because of his evil deeds, Ghenie’s sunflowers render visible the evil spirits of the time.

Already some three years ago, Ghenie’s engagement with the twelve darkest years of German history, and his fascination with the structure of evil led him to one of the most atrocious and incomprehensible figures of Nazi Germany – Josef Mengele, the camp doctor in Auschwitz, a man whom Ghenie chose to portray more than once. There are only a few extant photographs of one of the most sought-after criminals of all times, some of which are forgeries, and just like with the documents of the book burning-event, the fact that all the records of him are in black and white, and somewhat ephemeral, allows us to put great distance between ourselves on the one hand, and Mengele and his deeds on the other. But Ghenie had already been born, and Polaroid’s instant camera was sweeping the world, when Mengele finally died a natural death in Brazil in 1979. The painting The Arrival shows an older man in a heavy fur coat, standing before an exotic jungle scenery. The scene’s colorfulness is exacerbated by a suitcase painted in a neon-marker yellow. The title is ambivalent: it may refer to Mengele’s arrival in his final Latin American hideout. But also to the arrival of the evil that, for years after the fall of the “Third Reich”, continued being successfully exported to the world by networks of old Nazis and the CIA.

The exhibition is complemented by four paintings from the Pie Fights series. Ghenie presented the very first paintings from this series in our gallery in 2008, and they have since become nothing less than iconic. The original source of this series, which is an on-going development, are the pie fights of 1930s’ and 40s’ slapstick movies. To an artist who likes to apply paint in a manner that is both expressionistic and pastose, a face covered in dripping custard offers undreamt-of possibilities for parodying and expanding the classical portrait genre. To depict the victim of a pieing not just as portrait, but in space, further expands the artist’s options by involving at least two more genres: the interior and the history painting. Adolf Hitler’s oversized office in the Neue Reichskanzlei provides the frame of the two Pie Fight Interior paintings in our exhibition. In the years before the outbreak of the war, the “Führer’s” workplace was a popular subject for postcards. The figure in the large Pie Fight Interior 11 is clearly feminine – it could very well be Eva Braun. The intimate format of Pie Fight Interior 13 is strongly reminiscent of 19th century still lifes, and accordingly, Ghenie refers to it as “my Menzel”. It lacks figures, the obligatory flowers on the table, and the tapestry that Hitler famously loved so much. It shows his office after the “fall”, but not as a heroic ruin, but as that, which it always was: a large, but ultimately rather staid and dull room. The missing flowers we encounter elsewhere, in a painting that is rather unusual indeed for Ghenie. With Carnivorous Flowers, Ghenie has engaged with yet another traditional genre – the Pie Fight-Series, it seems, is can be further extended at will.

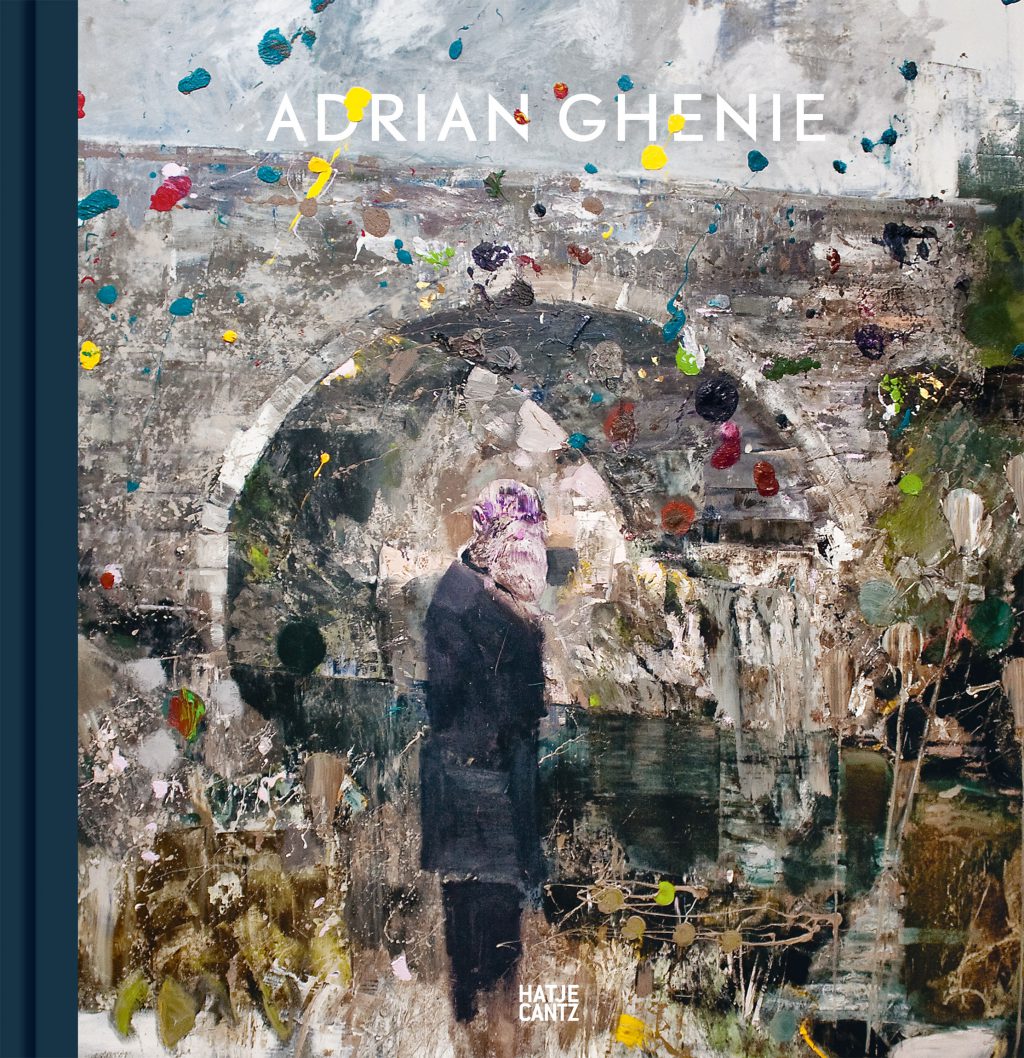

Catalogue

Edited by Juerg Judin

Texts by Mark Gisbourne and Juerg Judin

In English

275 × 280 mm

172 pages, hardcover

86 color ill., 5 b&w ill.

Published by Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern 2014

ISBN 978-3-7757-3674-9