Matthias Brunner

Magnificent Obsession – The Love Affair Between Movies And Literature

Works

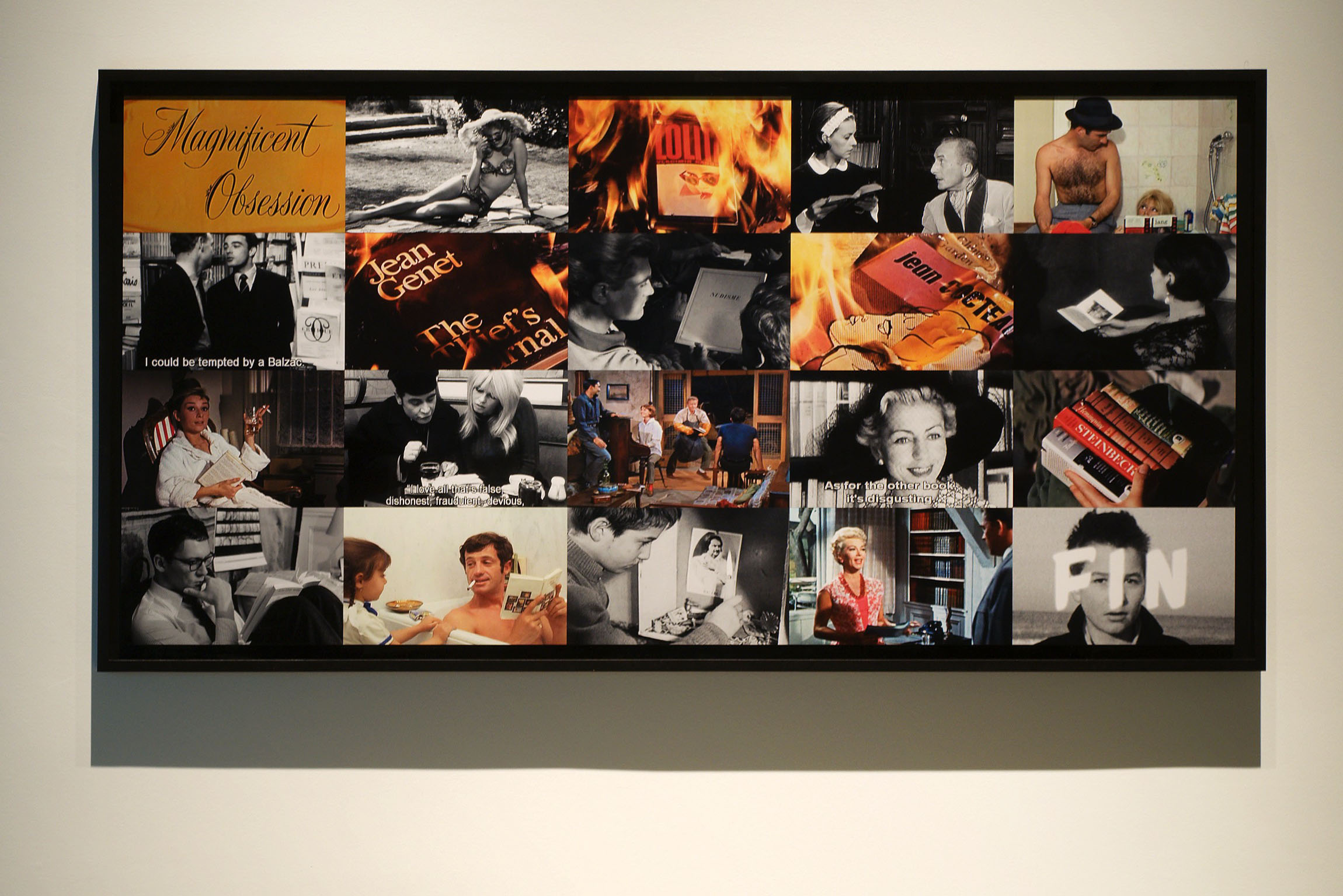

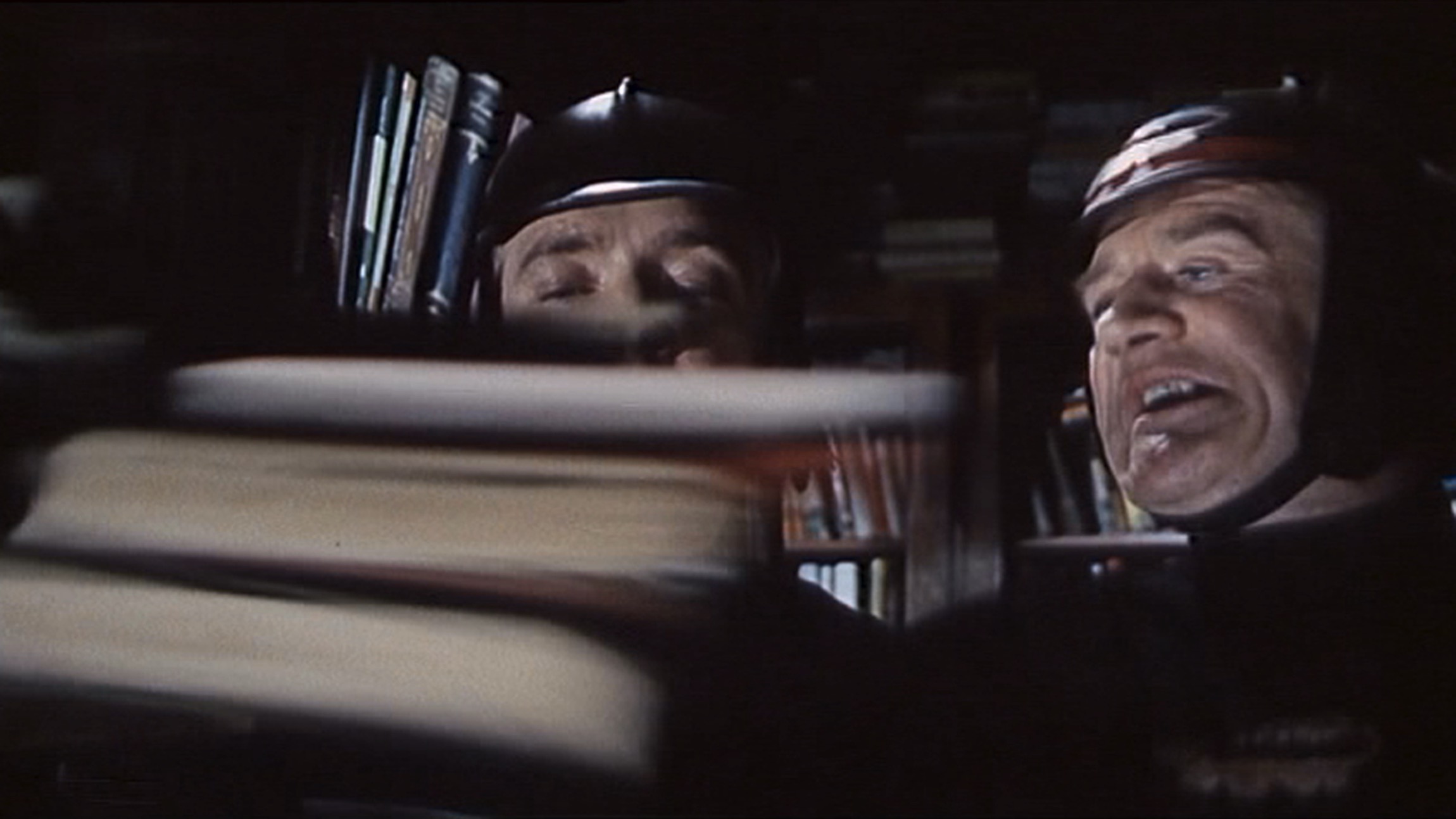

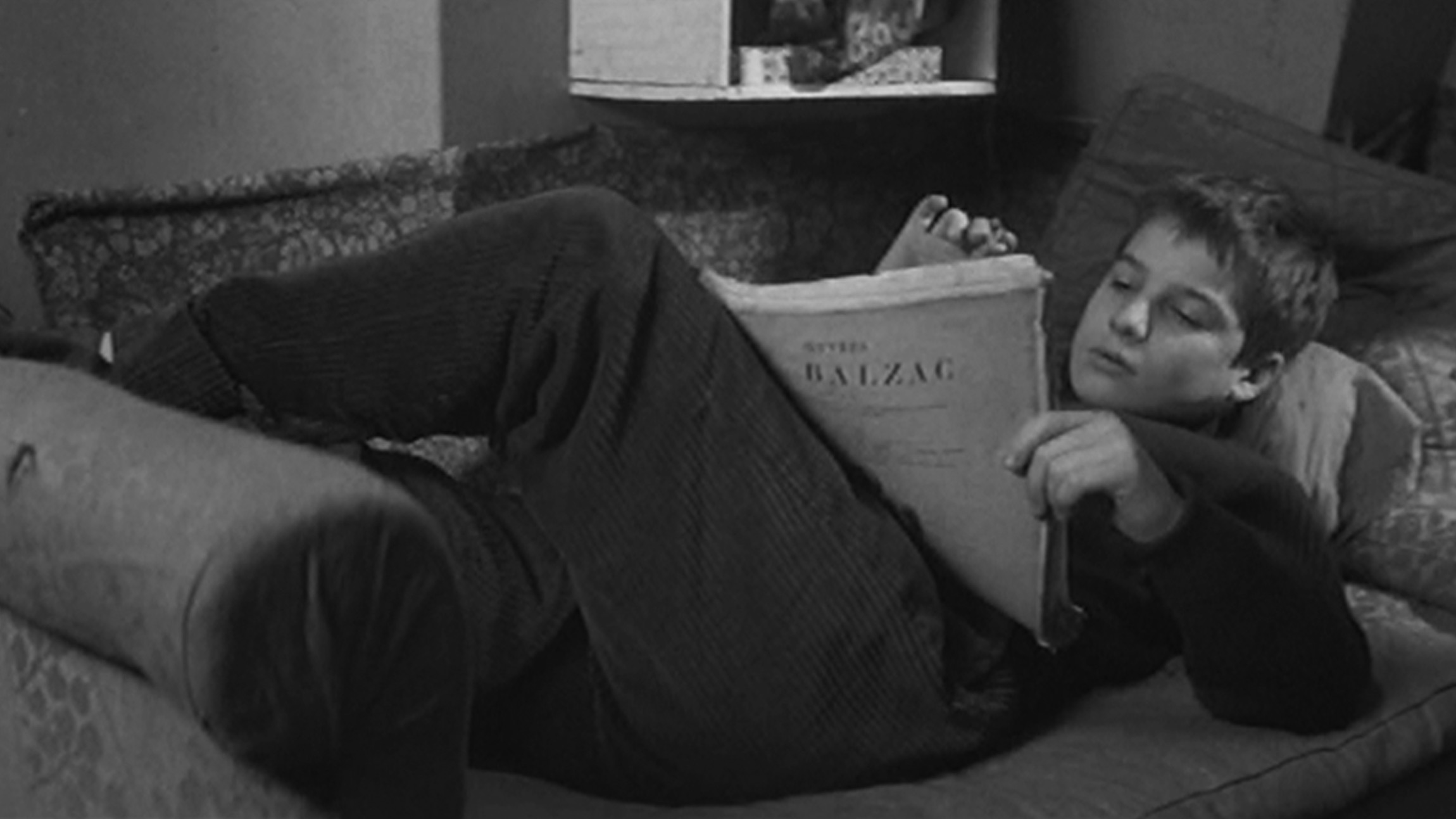

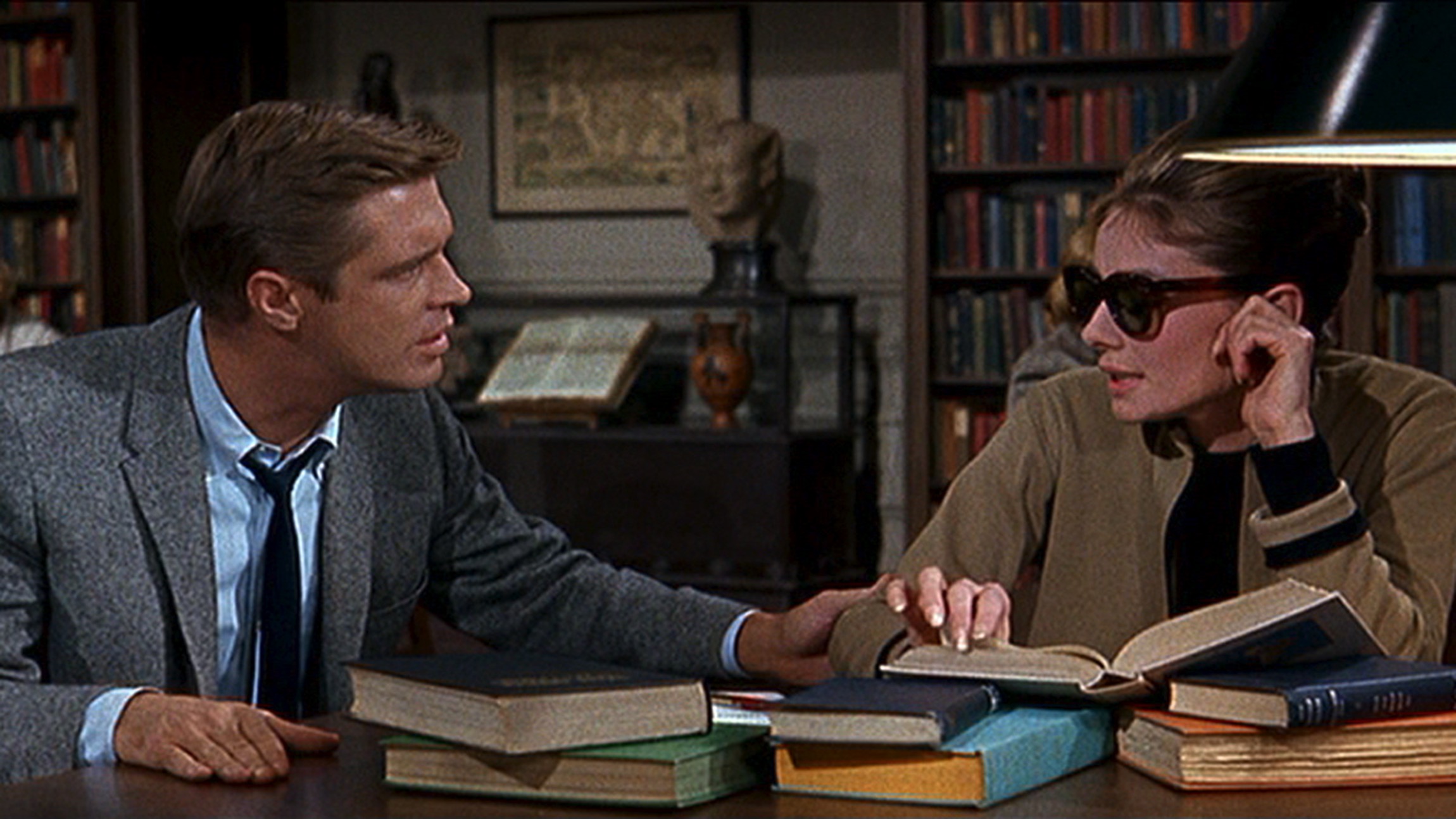

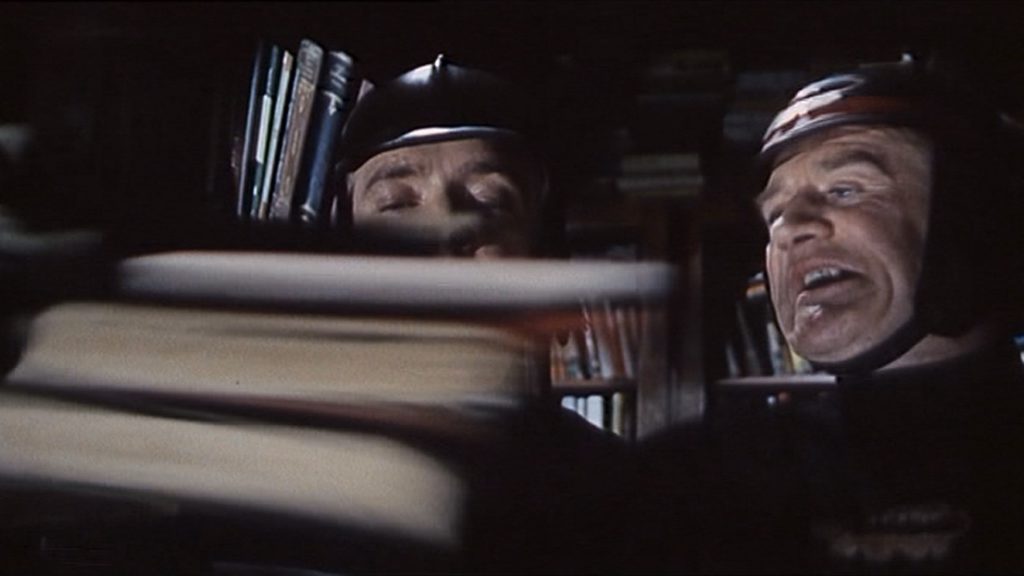

Magnificent Obsession (Still)

Magnificent Obsession (Still)

Magnificent Obsession (Still)

Magnificent Obsession (Still)

Magnificent Obsession (Still)

Magnificent Obsession (Still)

Magnificent Obsession (Still)

Text

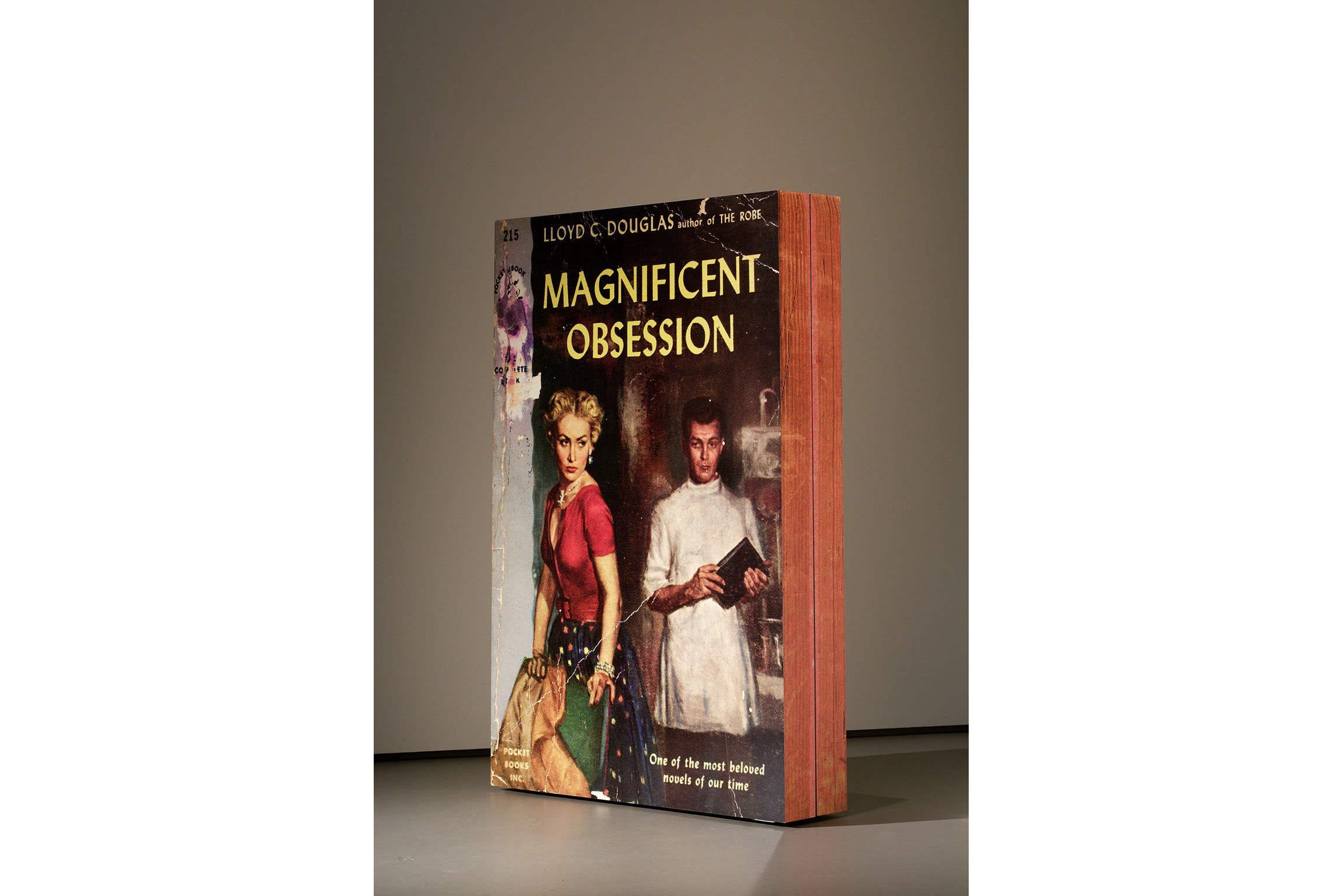

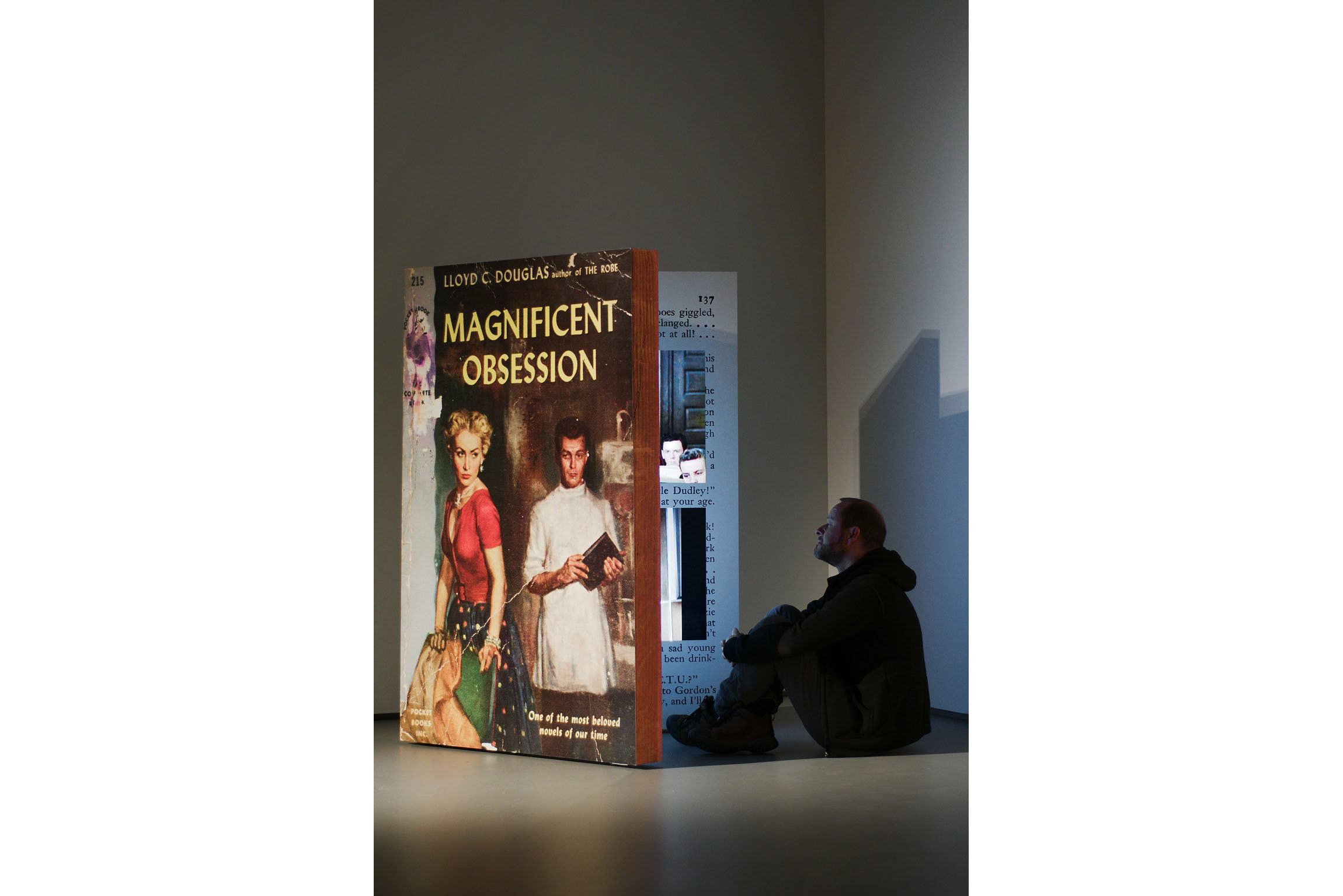

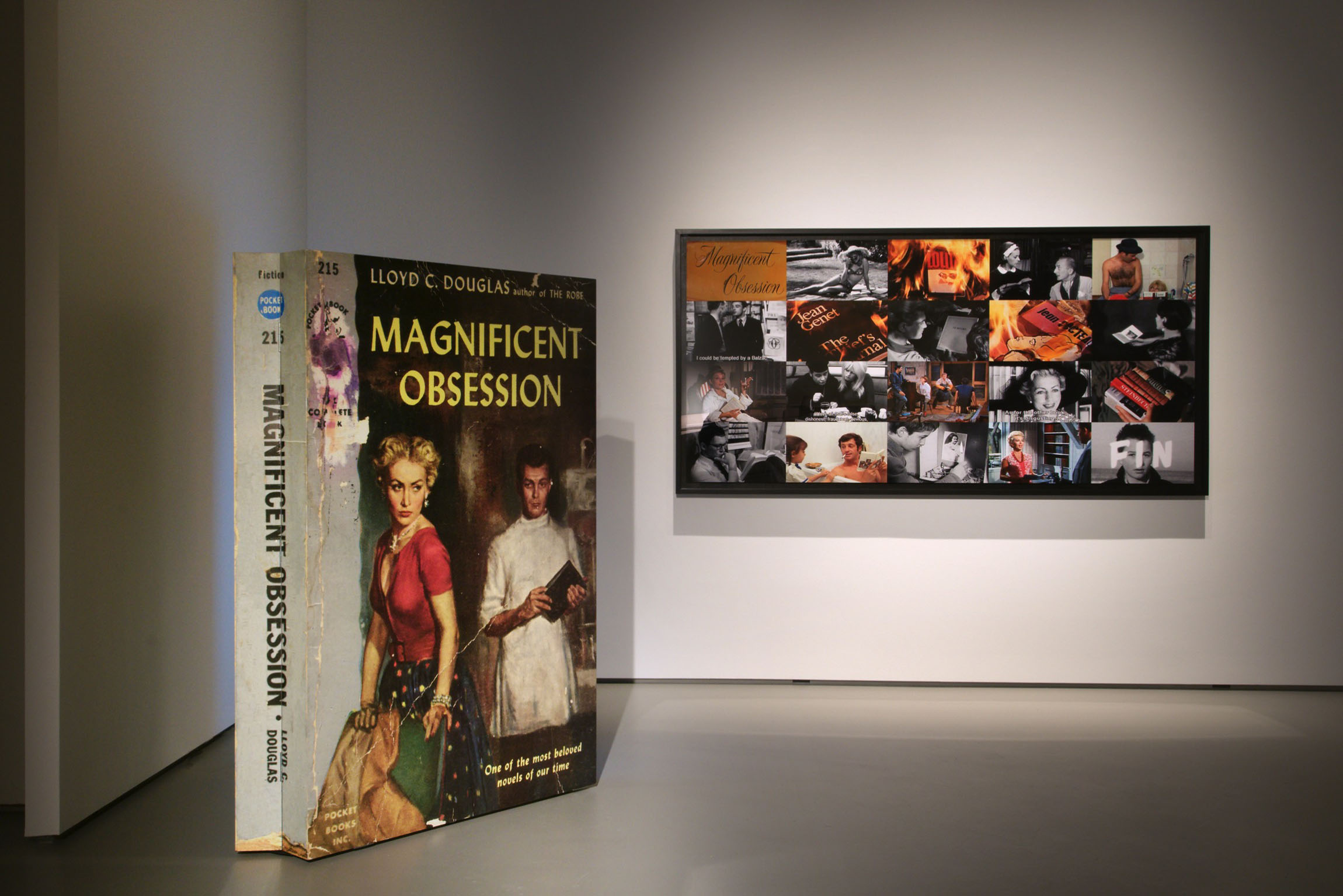

Galerie Nolan Judin is pleased to present the video installation Magnificent Obsession – The Love Affair Between Movies and Literature (2011/2012) by the Swiss artist and cineaste Matthias Brunner. Exhibited on the occasion of the Berlin International Filmfestival this is an ingenious and sensual compilation of clips from 36 masterpieces of European and American cinema from the 1950s and 1960s shown as a four-channel projection.

The love story of film and literature is almost as old as the history of cinema itself. As early as 1896 Louis Jean Lumière filmed a short version of Faust, and F. M. Murnau’s Sunrise from 1927, perhaps the most beautiful movie from the golden era of silent film, is based on a literary work, a novella by Hermann Sudermann – albeit a not very good one. And this was no exception. The list of great films based on second-rate literature is almost as long as that of the bad film adaptations of major literary works. Distinguished directors have failed miserably with books by authors such as Marcel Proust, James Joyce, Albert Camus, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and Patrick Süskind.

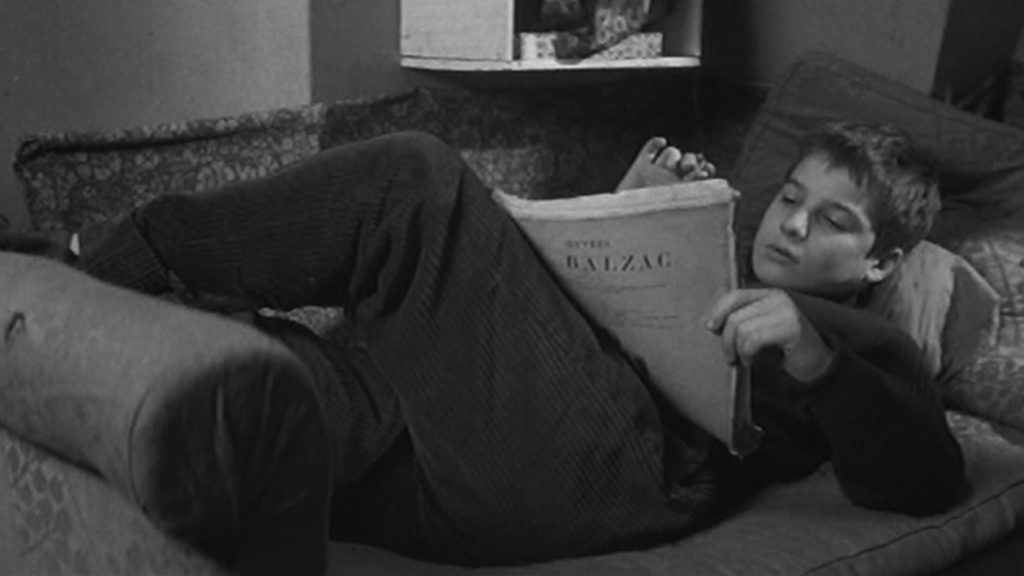

In no epoch, however, was the love affair between cinema and literature as intimate as in the period of the Nouvelle Vague, or New Wave. Starting in the late 1950s films were made based on the books of authors such as Alberto Moravia, Ray Bradbury, Henri-Pierre Roche, Adele Hugo, Marguerite Duras, Alain Robbe Grillet, Jean Cayrol, Jorge Semprun, and Dolores Hitchens. This is paradoxical, since the Nouvelle Vague was all about the auteur film, in which directors used their own material and screenplays to counter the predictable narratives of commercial cinema. But even if these directors did not create films based on (third-party) works of literature, their films convey a love of books—whether in a playful manner as in Une femme est une femme, as a philosophical discourse in Masculin-Feminin with Brigitte Bardot, or as an homage to the “petit policier” in Bande à part (all three works by Jean-Luc Godard). This focus on books is most intensively expressed in Les quatre cents coups by François Truffaut, in which the adolescent Jean-Pierre Léaud immerses himself so passionately in the works of Honoré de Balzac, that he allows his room to go up in flames. With this work Truffaut was fittingly nominated for the Oscar for best screenplay.

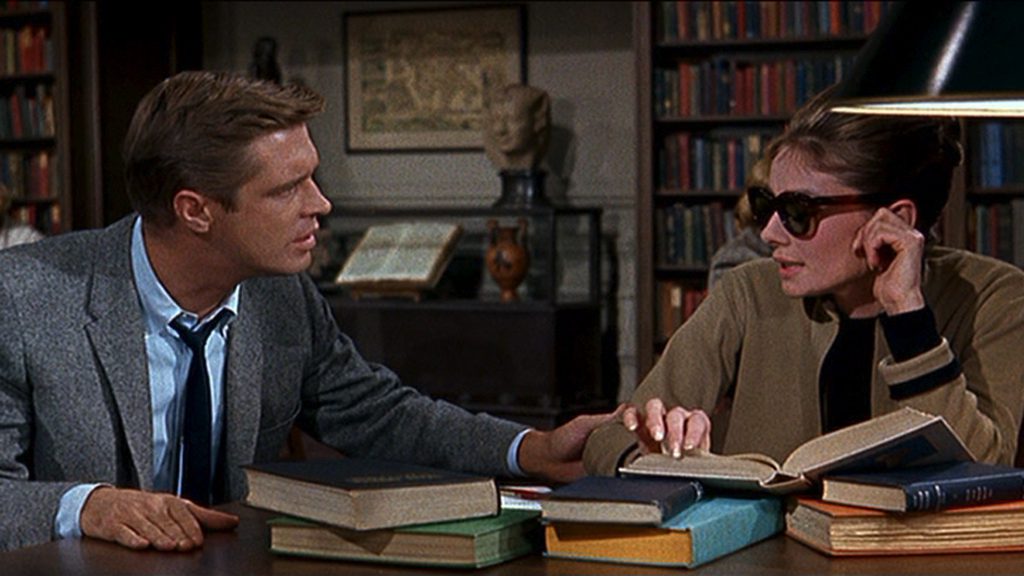

Continue reading

Nouvelle Vague films constitute the core of this installation. And since no “wave” can form without an initial impetus, segments of films from this period are placed in dialogue with films by Hollywood directors considered the seminal forefathers of the Nouvelle Vague. These include literary works adapted for cinema by directors who were masters of their craft: Alfred Hitchcock (The Birds, Marnie), Douglas Sirk (Magnificent Obsession, All That Heaven Allows, Imitation of Life), Elia Kazan (Splendor in the Grass), Vincente Minnelli (Some Came Running), Blake Edwards (Breakfast at Tiffany’s), Joseph Losey (Secret Ceremony), and Howard Hawks (Hatari!). But the Nouvelle Vague directors also had sources of inspiration in Europe: Max Ophüls (Letter To An Unkown Woman, Lola Montez), Luis Bunuel (Journal d’une femme de chambre, Belle de jour), Jean-Pierre Melville (Leon Morin Pretre), Luchino Visconti (Il Gattopardo), Jean Cocteau (Orphée), and René Clément (Plein soleil).

In watching hundreds of films from the 1950s and 1960s, Matthias Brunner noticed that whereas the Nouvelle Vague was passionately and playfully engaged with literature, American movies from the same period tended to borrow material from literature but without any in-depth examination of these literary sources and without making interesting plays on the texts—thus without any true declaration of love. Only a few American directors, including Douglas Sirk, Joseph J. Mankjewicz, John Huston, Vincente Minnelli, and Elia Kazan, were able to drawn on the full force of the books they used and do them justice. It is not by chance that these directors all had strong European roots.

With his installation Magnificent Obsession Brunner is by no means merely interested in an analytical investigation of this topic or an “assessment” of very different films. He avoids sequences of stereotypical topics and a confrontational comparison of European and American cinema. Magnificent Obsession is a highly associative, passionate, and poetic compilation of scenes from 36 films, which attempts to communicate the richness and complexity of the marriage between film and literature.

In the classic American film adaptations of literature, Brunner has not exclusively selected scenes featuring books, since the authors of the original texts seem to serve as sufficient reference, and other scenes seemed more important (for example in Magnificent Obsession, A Place in the Sun, Secret Ceremony). In contrast, with the Nouvelle Vague films, he found it important or almost essential to concentrate on scenes featuring books, texts, or authors, since these films are often closely structured around such key scenes.

Brunner has made an attempt to show as may aspects of the theme of the “book” as possible in his compilation: writing (Malle) and printing (Truffaut), the trip to the bookstore (Ophüls), a complaint about the book seller’s recommen-dation (Demy), the book as a store window display (Truffaut), book burning (also Truffaut), reading (Sirk, Godard, Truffaut), an encounter in a library (Edwards), the interpretation of a text (Kazan), and the caressing of a poem by the camera (Godard).

The viewer hears the sound of only one of the four simultaneously shown films. Brunner selected the soundtrack of the what he considers the most significant segment, but in a manner so that new and unexpected associations between the films develop in the process—intelligent and playful associations attesting to Brunner’s enormous cinematic knowledge and his very personal “magnificent obsession.”

Magnificent Obsession is part of the video collection of the Kunsthaus Zürich.